Breaking Down the Layers of the Immune System

It starts with a sneeze. Someone on the subway didn’t cover their mouth and now a cloud of invisible invaders hangs in the air. Before you even step off the train, your immune system has already begun fighting off the threat and protecting you from harm.

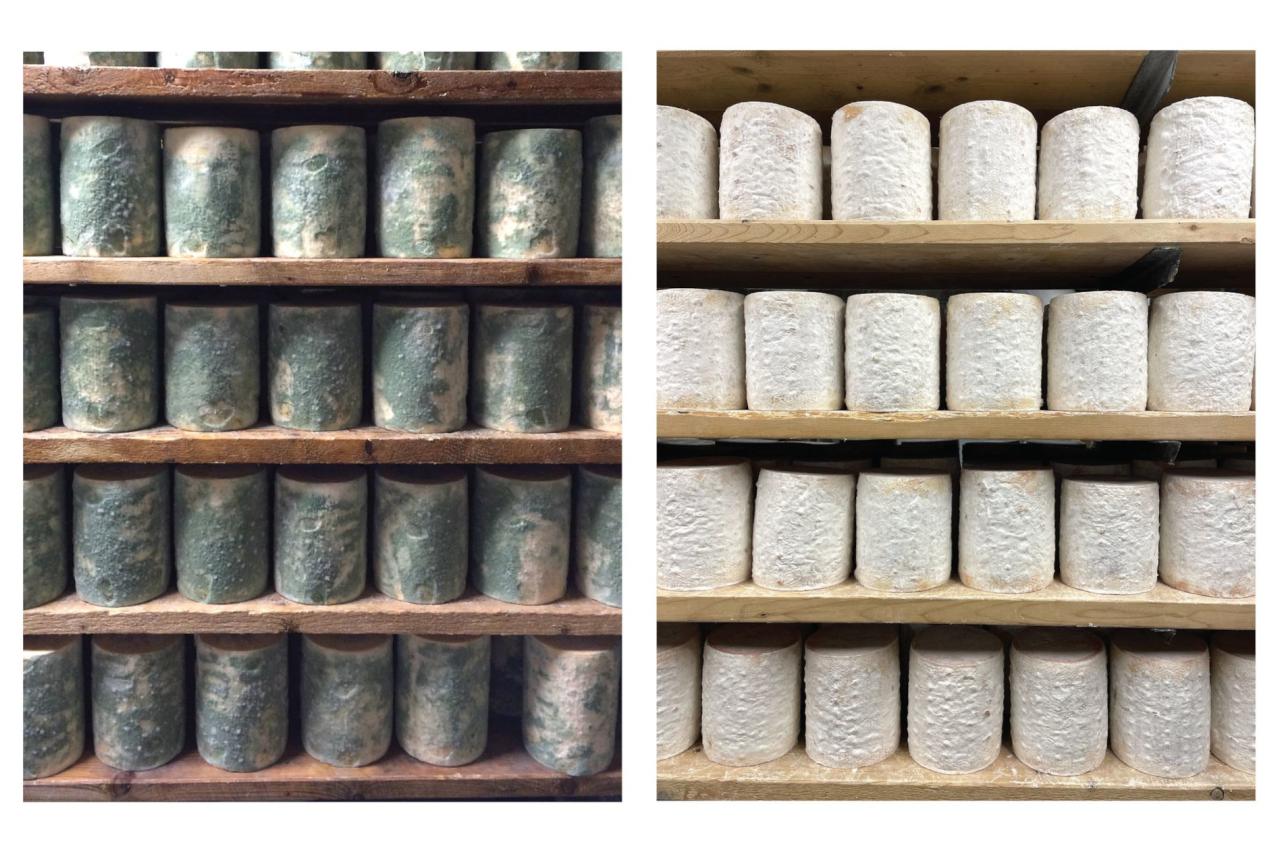

Imagine a high-tech security system, constantly scanning for intruders, identifying threats, calling for backup, neutralizing them, cleaning up the mess, and keeping detailed records for next time. That’s your immune system. But instead of lasers and alarms, it uses physical and chemical barriers and millions of cells to keep you safe.

“Immunity is a complex response that is broadly divided into two phases: innate immunity and adaptive immunity,” says Shruti Sharma, assistant professor of immunology at Tufts University School of Medicine, with a lab at the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences.

Barrier immunity is the first stage of the innate immune response and refers to the physical and chemical barriers that we produce to ward off persistent threats. Think of our eyes and their tears, our nose and its mucus, our stomach and its acid, our skin and its sweat. If these barriers are intact, the immune system passively protects us around the clock. But if these barriers are compromised (or the threat is too formidable), a second stage of the innate immune response is triggered like an SOS signal.

As soon as the barriers have been breached, the affected parts of the body send their immune cells to assess the threat, whether it’s a cut on your arm, a virus in your airways, or a foreign bacteria in your gut. The innate response’s job is to assess the threat and determine how best to handle it. When it has a firm grasp on the situation, and if it can’t deal with the threat itself, the innate response triggers the next phase of the immune system.

This second phase is called adaptive immunity. Where innate immunity stays agile and nonspecific so that it can catch everything, adaptive immunity is more fine-tuned and applies specific tactics to each unique threat. For example, it can tell the difference between pneumonia and bronchitis (both bacterial infections) and deploy different methods of attack for each. Once the adaptive response takes care of the threat, the innate response is called back in to clean up the mess, disposing of dead cells in damaged tissues, and ultimately signaling an end to the immune response.

Illustration: Shutterstock

But everyone’s immune system responds differently to the same threat. The person standing next to you on the train when another passenger sneezed might be sick for far longer or experience worse symptoms if their immune system has been compromised.

So how do we optimize our immune systems and what compromises them in the first place?

The Factors of Immunity

The body’s ability to fight an infection or other threat depends on whether or not it has been exposed to the threat before and the resources available to it when the threat comes knocking. Fighting a threat takes energy. It takes cells and blood and water. So when the body is already depleted, its resources will be exhausted before the threat is fully dealt with. A deprived system stays in a prolonged state of weakness, leaving the infected person more sick for a longer period of time.

Some of the body’s resources are fixed while many others can be controlled by our choices. One fixed factor that determines each person’s immune response is genetics: innate immunity is primarily genetically encoded. Nothing much we can do about that.

Our environment also impacts our immune system’s ability to fight infections. Air pollution or toxins in our food or water have their own potential negative health impacts, and also weaken our body’s ability to defend itself from other threats like the flu. Wildfire smoke and other climate-related extremes can also impair the immune system by weakening cell linings, essentially weakening the body’s fortifying barriers.

Even if we can’t control our exposure, genetics, or environment, there are many ways to fortify the immune system so it’s ready for the next threat. Plenty of water, a balanced diet, supplements, and regular exercise keep the body’s natural processes functioning at their highest levels.

“Most biological processes require water, so drinking plenty of water ensures all your cells have enough to perform protective functions if and when your body is exposed to a threat,” Sharma says.

The vitamins, minerals, and macro- and micro-nutrients found in a healthy, balanced diet supply the body with the fundamental tools needed for a robust and ready immune system. Though supplements may be necessary for some people, and supplements like vitamin C may strengthen key cells involved in the immune response, Sharma says taking supplements when you are already sick often doesn’t offer the same benefits. Once the barrier has failed and the infection is inside, fighting it off may require processes that have adapted to the absence of vitamin C or might even be impaired by a sudden influx of vitamin C.

Lastly, getting regular moderate exercise can improve the immune system’s ability to fight off infection. Exercise improves the lungs’ ability to function and recover during stress while also promoting blood flow and the circulation of immune cells.

Considering the many factors involved in determining each person’s immunity—genetics, exposure, environment, diet, hydration, exercise—and all the energy it takes to fight an infection, there’s no better time than the present to prepare for cold and flu season. So, drink water, eat your veggies, and take a walk. You’ll thank yourself later.