The Wizard Behind Wicked

Music and magic—and some big questions about the nature of evil—will fill theaters worldwide this November as the much-anticipated Wicked: For Good hits the big screen. The film will continue the tale of the green-skinned girl Elphaba who becomes Oz’s Wicked Witch of the West.

The movie is the sequel to last year’s Wicked, which was nominated for 10 Academy Awards and broke box-office records for film adaptation of a Broadway musical. Both movies are based on a wildly successful show that’s been on Broadway for more than 20 years.

“Wicked has just become this phenomenon. It’s a show-stopping spectacle, a celebration of women, and an astonishing commercial success,” said Barbara Wallace Grossman, AG84, Professor of Theatre and Performance Studies at Tufts, who teaches The American Musical – Radical Acts and Adaptations, a course she created.

Beneath the glittery surface, the show probes questions about power and marginalization that have deep resonance today, said Susan Napier, Goldthwaite Professor of Rhetoric in the International Literary and Cultural Studies Department at Tufts. “Blockbusters hit a lot of different nerves at the right time,” she said. “When something is mega-popular like that, it means something is going on in our society.”

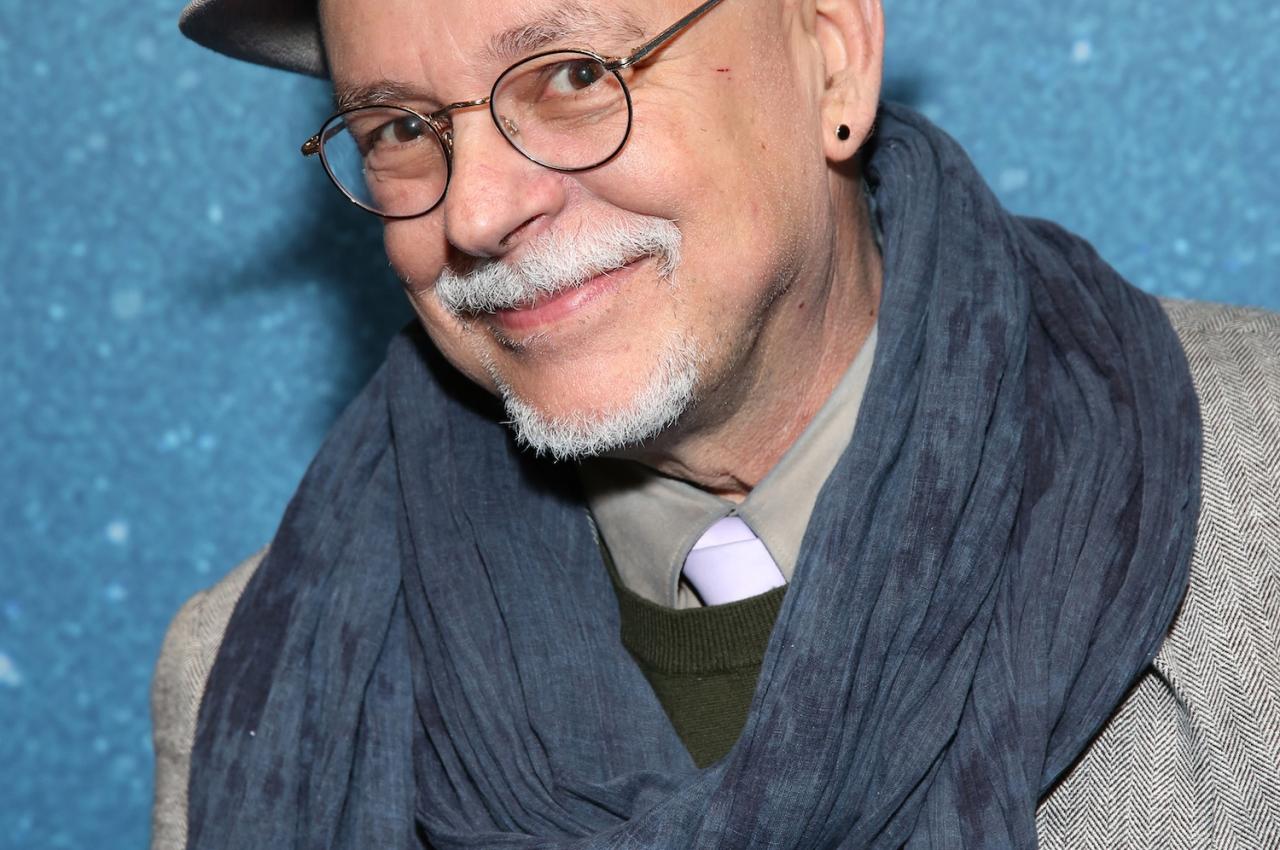

The questions aren’t entirely new, though. You see, even before the movie and the musical, there was a book. And behind the book, there was a man: Gregory Maguire, AG90, whose story—minus the evildoing and verdigris—is remarkably like Elphaba’s.

Some Things I Cannot Change

Maguire’s childhood reads like a fairytale. His mother, Helen Maguire, died from childbirth complications a week after bringing him into the world. After a stint in an orphanage, Maguire was reunited with his father and stepmother—his birth mother’s best friend, whom he came to call his second mother.

He grew up in a Catholic family in Albany, New York, in the 1950s and ’60s, the middle of seven siblings. He has described wrestling with feelings of guilt about his mother's death and believing that his own life had to be twice as fruitful to compensate for her loss.

His refuge was his local public library, built in a Dutch Renaissance style—a magical place that felt and smelled like a castle to him. Its children’s room featured a stone staircase built into a circular tower. His second mother, a poet, checked out 40 or 50 books for the family at a time

Maguire sympathized with the frozen, suffering animals of the Chronicles of Narnia, and cried when Meg Murray saved her little brother Charles Wallace in A Wrinkle in Time. After reading Harriet the Spy, he got himself a spy’s notebook.

Maguire read L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, published in 1900, and religiously watched the 1939 movie with his family when it aired on TV—inspiring nightmares of the Wicked Witch of the West and games in which Maguire had his siblings play all the characters—often switching characters’ genders, bringing in villains from other stories such as Peter Pan’s Captain Hook, and holding contests for the most evil.

Fantasy tales gave Maguire identity and escape, especially as he realized in his teen years that he was attracted to other boys.

He moved to Boston in the 1970s to study children’s literature at Simmons College, where he earned a master’s degree in 1978. After publishing the children’s book The Lighting Time, he earned his doctorate in English and American literature at Tufts, where his thesis advisor, the late Martin Green, treated children’s literature as a legitimate branch of adult literature.

Another Tufts professor, the late Jesper Rosenmeier, taught Maguire in a course on Puritan and Colonial literature about developing tolerance for history’s complications and avoiding jumping to conclusions.

These experiences would later inform the creation of Wicked.

No One Mourns the Wicked

When the Gulf War was starting in the early 1990s, Maguire was living in London. He saw a headline: “Sadaam Hussein: The New Hitler?” and felt his blood temperature drop. Just the word Hitler evoked a powerful sense of evil.

Then in 1993, two 10-year-olds murdered a 2-year-old in Merseyside, England, which made many— including Maguire— wonder about the source of such unfathomable behavior. Maguire asked himself what constituted evil. Would actions that stemmed from deprivation or an unsound mind count?

“I set out to find a definition of evil that might be accurate in any instance,” he said.

Hesitant to write about Hitler or the Merseyside case, Maguire instead thought back to a famous, fictional evil character: the Wicked Witch of the West. Baum had written her as a “small, crabbed, madwoman of a witch,” Maguire said, while actress Margaret Hamilton had played her in the 1939 movie as “conniving, smart, strategic, and vindictive.” Yet he felt there was more to her than people knew.

He remembered a scene in the 1939 movie where the nameless Wicked Witch of the West calls the Good Witch by name, Glinda. What if the two had known each other for a long time? What if they had gone to college together, perhaps had been roommates even? He laughed so hard at the idea that he actually fell down.

Thus, on his 39th birthday, Maguire finally felt prepared to begin writing his first novel for adults. His Oz was a land of social and political unrest, and a wide spectrum of landscapes, languages, beliefs, and sexual orientations. His Wicked Witch of the West was a mix of the previous book and movie versions.

“Elphaba ended up being slightly maddened by moral panic, bright, and committed,” he said. But she was also more: “To this I added the sad reality that she wasn’t very successful at her many campaigns, though her heart was in the right place.”

Like Maguire, Elphaba spent much of her childhood feeling alienated and alone, and her mother died from childbirth complications (though in her case it was after a later child’s birth). But although Maguire’s book subtly raises questions about Elphaba’s biological sex, and many readers have perceived erotic tension between her and Glinda, her green skin and ostracization are a metaphor for more than her sexuality or his own, Maguire has said. They are analogs for the human experience, in which we’re all different and sometimes feel like we don’t quite fit in.

As Maguire considered what linked Elphaba with others who are thought of as evil, he speculated that “an element of self-hatred is part of the combustive fuel that eggs the behavior on.”

Maguire’s hoped-for definition of evil? “I could not come to a conclusion,” he said.

Original cover of Wicked

Are People Born Wicked?

Published in 1995, Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West was more than 400 pages long. With its philosophical bent and characters who weren’t all likeable right away, the book was complex and required time and thought, Napier said.

“You really can't go into it thinking ‘Oh, this is going to be fun. I'm just going to enjoy myself,’” she said.

The novel didn’t take off immediately. A review in The New York Times complained about Maguire’s politicization of beloved characters.

But other forces were in motion. “It was the start of a great wave of fantasy that was crashing along the shores of mainstream culture,” Napier said, citing the Harry Potter books (which debuted two years later) and the Lord of the Rings movies (launched in 2001).

Also, the very things that made Wicked tough to get into made it stand out from other fantasy. Maguire’s Oz was richer and more real than other realms, Napier said. Not clearly heroes or villains, Maguire’s characters were multilayered and fundamentally human. “He's one of the people who injected that contemporary form of literary expertise into his books,” Napier said. It was brave and provocative to take on a villain as iconic as the Wicked Witch of the West, Napier said—and Maguire did it for a reason. “He’s using Wicked and Oz as a way to think about what it's like to grow up marginalized. He was doing something very ambitious and groundbreaking,” said Napier, who finds Elphaba a much more compelling heroine than Baum’s child heroine, Dorothy.

Far from being an escape, fantasy offers an arm’s-length perspective on reality that can take us deeper into it and help us process it, Napier said. “Seeing Elphaba with her green skin, which is magical and a sign of her powers but also means she is bullied and ostracized, we can work through our issues about belonging.”

Yet Maguire doesn’t offer his readers simple answers or a happy ending. Instead, he suggests that “it’s tough stuff, being in a world that’s increasingly tangled and complicated, hard to understand, and dark,” Napier said.

A Chance to Fly

Despite the novel’s complexity, a positive review sparked a flurry of interest, and the book was optioned for a film.

An initial attempt at making a movie stalled, but in the early 2000s, composer Stephen Schwartz—whose previous hits included Godspell and Pippin—argued to change it into a stage musical. Everyone sings in Oz, he said, pointing to the 1939 Wizard of Oz film. The original book had also inspired a 1974 Tony-winning musical, The Wiz, which was made into a 1978 movie; a recent revival of that show is now on a North American tour.

Photo by: Shutterstock

Maguire chose not to be involved in the Wicked production, which opened in San Francisco in May 2003 and premiered on Broadway that October, bursting with whirling dance numbers and special effects including flying monkeys and a dragon.

Maguire had seen that Schwartz understood the novel’s serious message and trusted him to translate it to the stage, even as the story’s central elements—from the characters to the mood to the plot—changed dramatically. For just one example, the musical turned Elphaba’s married schoolmate Fiyero, with whom she has a complicated relationship in the book, into a swoonworthy (and single) prince and their relationship into a sweeping romance with a happy resolution.

The musical has “visually spectacular effects and songs you can remember and sing, comic elements but also a seriousness to it, a complexity to the characters,” said Grossman, who had read Maguire’s book before seeing the musical and thought it was “marvelously transformed.”

The show received mixed critical reviews but became a fan favorite, partly because it played up the friendship between Elphaba and Glinda, whose duets “Popular” and “For Good” became talent show mainstays.

“Their relationship is fraught in the beginning, but they really come to respect each other and grow, and value each other’s friendship,” Grossman said. She pointed out that Elphaba takes her fate in her own hands at the end of the musical, while Glinda ends up a leader. “It’s a satisfying female relationship that doesn’t require marriage as a resolution for either of them,” she said.

Elphaba in particular is compelling because she’s a bit of a misanthrope, Napier said. “She’s not sweet. She strides around and doesn’t play into people pleasing.”

Not to mention she’s the villain. “There’s fear, fascination, and excitement in a woman who is not in her place, who is not nurturing, who pushes against all our known constrictions,” Napier said.

In a departure from many other fantasies, the musical showcased female power—literally, with Elphaba rising into the air at the end of the first act. The metaphor appeals to women and anyone who has felt like an outsider, said Napier. “There's a deep-seated longing for this kind of agency and power, to be above and away from everything and to look down on the rest of the world and have a sense of control, at least of yourself,” she said.

Maguire was stunned and energized by the first public performance of Wicked, particularly the song “Defying Gravity” and Elphaba’s raging second-act belter “No Good Deed,” and went on to see the show dozens of times. The Broadway version of his characters and story became world-famous, inspiring Halloween costumes, karaoke performances, graphic novels, and decades of dedicated fandom.

Poster for upcoming movie Wicked: For Good

Looking at Things Another Way

The 2024 movie Wicked embellished upon the musical, including only its first act with slightly different plot points. The trailer for the second movie, which covers the second act and will feature two new songs, was viewed online more than 113 million times in its first 24 hours, surpassing the hype for the first installment.

The director, Jon Chu, has expressed interest in exploring more of Oz as imagined by Maguire, whose Wicked Years series includes Son of a Witch (following Elphaba’s son), A Lion Among Men (centering on the Cowardly Lion), and Out of Oz (featuring Elphaba’s granddaughter). During the pandemic Maguire also wrote a sequel series—and this year, he explored Elphaba’s earliest years in his latest novel, Elphie: A Wicked Childhood.

Reflecting on his three-decade relationship with Elphaba, Maguire said she’s a version of himself. “We share a certain moral fervor, though that sounds boastful to admit. We also share a streak of ineffectuality at using our strengths to the greatest good, despite where our hearts lead us.”

These days, Maguire and his husband, the painter Andy Newman, who are the parents of three adult children, split their time between Massachusetts and France. The publicity around the Wicked movies has sometimes been overwhelming, but it has prompted Maguire to reflect on how much his exploration of social and political unrest, power, and morality still fits the times.

“As we have become more destabilized as a society and as a comity of nations, my work has gone from being retro to being prophetic,” he said. “The portrait of Elphaba’s resistance speaks even louder than it did 30 years ago.”