Can AI Be Conscious?

We read and speak and routinely have complex thoughts—and now AI seems to do the same. We are conscious beings; are AI models conscious, too?

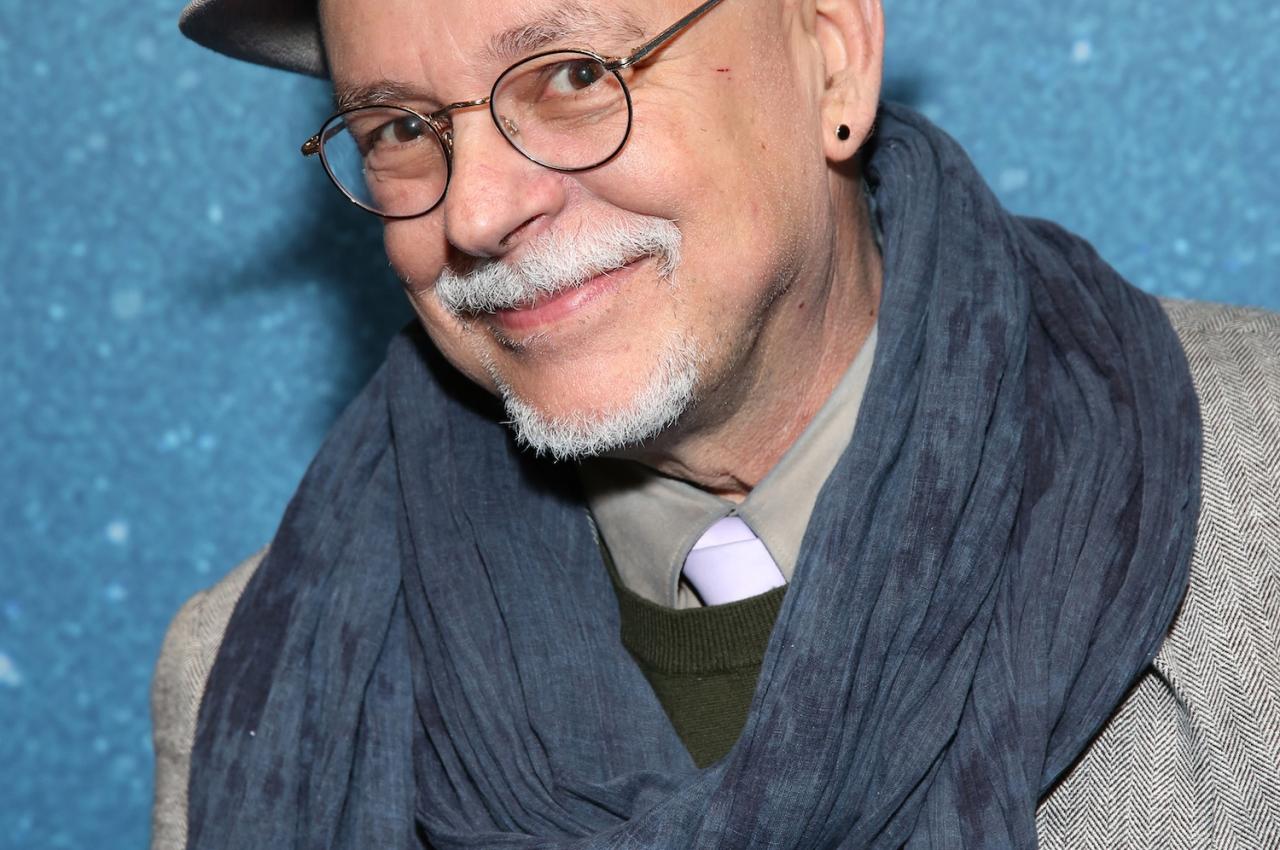

That question was one of the main focuses of a symposium in honor of Daniel C. Dennett, the internationally noted philosopher and longtime Tufts professor, who died in April 2024. The gathering brought together renowned faculty from around the world, who all had a connection with Dennett—even if the connection sometimes took the form of intellectual sparring.

The symposium, Let’s Talk About (Artificial) Consciousness: A Day of Study Honoring Dan Dennett, was organized by Ayanna Thomas, dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, along with the Office of the Provost, and held on October 14.

“Dan was a huge figure in philosophy and cognitive science for the last 60-plus years, and he was a huge figure in the lives and in the work of so many of us here and so many people around the world,” said David Chalmers, University Professor of Philosophy and Neural Science at New York University.

Dennett’s ideas were “so formative to how everybody thinks about everything from consciousness through intentionality, through belief, through free will, through evolution, through religion,” he said. “It was an honor to be his adversary, and it was a privilege to be his friend.”

“Dan shifted the intellectual landscape in ways that are almost invisible,” said Brian Epstein, associate professor of philosophy at Tufts and a colleague of Dennett’s. “Many of the assumptions common across philosophy, psychology, neuroscience, and AI bear his fingerprints, even when people don’t realize it.”

Another aspect of his work “is that he did so much to bring philosophy and science together,” said Anil Seth, professor of cognitive and computational neuroscience at the University of Sussex. “I think that ability to do that—to bring together what should always be together—may be his most significant legacy of all.”

Dennett was a public intellectual and wrote many popular books, including Consciousness Explained and Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, gave TED talks with millions of views, and won the 2012 Erasmus Prize for exceptional contributions to culture, society, or social science.

He taught at Tufts for almost 50 years, always offering classes to undergraduates. One such student was Michael Levin, A92, Vannevar Bush Distinguished Professor of Biology at Tufts. “Partly why I came to Tufts is because I thought there might be a chance to learn from Dan in person,” he said.

He recalled how Dennett spoke critically in the Philosophy of Mind class about theories of dualism—the separation of mind and body—and approached Dennett with some trepidation, saying he wanted to write a paper defending dualism.

“He said I should absolutely do it. I was just amazed how he took it seriously, and he helped me make the best version of it, even though I knew he hated the idea,” Levin said. “It was an example of what intellectual honesty looks like. It really helped nourish in all his students this idea, the ability to pursue and publish and defend unpopular ideas.”

Among the speakers were Chalmers; Anna Ciaunica, senior research fellow at the Centre for Philosophy of Natural and Social Science at the London School of Economics; Felipe De Brigard, AG05, professor of philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience at Duke University; Seth; Susan Schneider, William F. Dietrich Distinguished Professor of Philosophy and director of the Center for the Future Mind at Florida Atlantic University; and Giulio Tononi, professor of psychiatry and distinguished professor of neuroscience at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Tufts-affiliated faculty speakers included Epstein; Ray Jackendoff, professor emeritus of philosophy and Dennett’s former co-director of the Center for Cognitive Studies; Gina Kuperberg, professor of psychology and psychiatry; Levin; and Matthias Scheutz, Karon Family Applied Technology Professor of Computer Science.

What Exactly Is Consciousness?

Questions of what constitutes consciousness—in humans and machines—was a recurring theme at the symposium. Chalmers spoke about the frequent emails he receives from strangers telling him about interactions they have had with AI large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, which lead them to question whether the chatbots are conscious.

“Are they right that this is genuine awareness, creativity? Well, maybe not, but something is going on,” he said. “Is it at least something with beliefs and desires? Is it a computer? Is it a mere algorithm?”

At the morning session panel of the symposium, from left, Michael Levin, Matthias Scheutz, David Chalmers, and Brian Epstein. Photo: Alonso Nichols

The current large language models “are most likely not conscious, though I don’t rule out the possibility entirely,” Chalmers said. “My own view is that when you talk to an LLM, you are talking to a quasi-agent with quasi-beliefs and quasi-desires, implemented as a thread of neural network instances.”

But future language models and their descendants “may well be conscious. I think there’s really a significant chance that at least in the next five or 10 years we’re going to have conscious language models and that’s going to be something serious to deal with.”

He cautioned, though, channeling Dennett’s concerns, that while “the fact that it’s possible to create an AI system with these extraordinary capacities is intellectually amazing, practically and ethically and prudentially, just because these things are possible doesn’t mean we should create them,” echoing Dennett’s strong fears of “counterfeit people.”

Seth, author of Being You: A New Science of Consciousness, was less sanguine about the possibility of conscious AI. “I think the role of language here is really highlighted by the fact that pretty much nobody thinks that AlphaFold from DeepMind is conscious,” he said. AlphaFold is an AI system “that solved the notoriously difficult protein folding problem in biochemistry,” and is based on the same “transformer-based architectures with some other bells and whistles running on silicon” like LLMs such as ChatGPT.

But “it doesn’t speak to us, so we don’t tend to project into it these same things [like consciousness], even though under the hood it’s pretty much the same kind of thing,” Seth said.

“This may be a little bit more cynical, but the more that big tech companies can make AI seem like magic rather than just a sort of glorified spreadsheet, the easier it is to continue justifying the huge amounts of investment and salaries that we see in that area—the money keeps on flowing,” he argued.

Like Chalmers, Seth also gets emails from people saying they think the chatbot they interact with might be conscious. “We are predisposed to think this way,” he says. “We come preloaded with a bunch of psychological biases which lead us to attribute—or over-attribute—consciousness where it probably doesn’t exist. We tend to put ourselves at the center of the universe and see things through the lens of being human, which means that if something behaves in ways that seem to be distinctively human, then we project into it other qualities which we associate with humans. And we do tend to associate intelligence and consciousness together.”

After all, he said, “we know we are conscious, and we like to think that as a species we’re intelligent, despite evidence of the contrary.”

That said, “it might be that computational functionalism is correct and if we build an AI system that implements high audit theory or global workspace theory, it’s conscious,” Seth said. “So, it’s possible. Nobody knows what it takes for a system to be conscious. There’s no consensus on the sufficient and necessary conditions. So we have to be open to that possibility—and that will be ethically problematic.”

Losing the Battle With AI

Seth cautioned against trying to create conscious AI. Doing so would “distort our moral circle of concern, and we may end up caring less about things that really deserve our moral consideration.” Several speakers pointed to concern that the AI company Anthropic is showing for its AI model Claude—the LLM, not the people using it.

In his work, Dennett argued that “we should treat AI as tools rather than colleagues and always remember the difference,” said Seth.

“He called them people imposters, not like humans but that sound like humans, but don’t have inner lives,” said Scheutz, a computer scientist who focuses on human-robot interaction. “They’re more like viruses that exist as parasites, that we help to replicate and evolve.” And “regardless of whether you believe that these models are conscious or not, they are getting more and more capable and they’re becoming very, very manipulative.”

Scheutz also cautioned about considering AI models to be conscious in any way. “Based on many, many tests that we can do, these models are incredibly smart,” he said. “They’re very good at answering and performing at superhuman levels on these tests. But are these models conscious in any meaningful way? I want to say no, because [while] they learn and embody very complex mappings, there’s otherwise no internal activity in these models. There’s no self-sustaining activity that I take to be a prerequisite for a system to be aware of the environment and the work itself.”

The deep fakes that generative AI are creating are disturbing, says de Brigard, who studied with Dennett while earning a master’s degree at Tufts and maintained a close academic connection and friendship with him long after graduation—Dennett even officiated his wedding.

De Brigard’s research focuses on the way in which memory and imagination interact, and he noted that “our deception detectors—both the automatically involuntary and unconscious, as well as those controlled and voluntary—are insufficient to identify deception in artificial intelligence.” The speed of the evolution of AI deception is much faster than humans’ ability to evolve biological and cultural AI deception detectors, he added.

“I would like to say that we’re losing [that battle], but I don’t think we’re losing. I think we’ve already lost,” de Brigard said. He thinks humans’ abilities to predict behavior of rational agents “is insufficient to help us detect and to deflect deception in contemporary and future artificial intelligence.”

His hope was that eventually “we’ll learn to avoid interfaces that can be tainted by AI and that we will go back to good, old-fashioned one-to-one interactions.”

Schneider, who gave the closing address, noted that when she opened her Center for the Future Mind, Dennett was her first invited speaker, talking on the topic of counterfeit people, a concern of his which he later articulated in a widely read article in The Atlantic.

He argued that the widespread creation and use of deep fakes with AI poses an existential threat to civilization by destroying the basis of trust in society. Dennett, she said, “was so intellectually brave, and he knew exactly what to say about an important ethical issue without waiting for other people to say it first.”

LLMs, which function “as a sort of crowdsource neocortex,” are double-edged swords, Schneider said. “They’re really exciting. I think from the vantage point of science, I am actually quite optimistic in terms of machine intelligence. What I’m worried about is who has the keys to the machine intelligence and what we’re going to do with it. And I think Dan saw it coming. He knew we shouldn’t build seemingly conscious AI.”