Daniela Koplin’s DNA Matchmaking

Daniela Koplin, A26, a double-major in community health and psychology who interns in a genetics lab, believes the cures for many devastating diseases can be unlocked through genetic research. But she is already seeing the real-world power of genetics as the Tufts representative for Gift of Life, a volunteer organization that matches blood cancer patients with stem-cell donors. She’s swabbed hundreds of Tufts students and made three potentially life-saving matches. She takes inspiration from a pioneering researcher from the dawn of DNA discovery: her own grandmother.

What ignited your passion for genetics?

My grandmother, Dr. Jean Hentel, was a major influence in my life. She earned her PhD in genetics when the field was very new. DNA only had been discovered a few years prior, and it was pretty rare for a woman to pursue a career in this field.

She was very strong-willed and would always speak her mind. If there was a spider in the house, she’d just go over, pick it up with her hand, and move it away. She wasn’t scared of anyone or anything.

She focused on blood cancers. Beyond the science, she had a deep love for the familial side of genetics. She would trace family trees, keep in touch with distant cousins, and was always thinking about the connections between people, both biologically and emotionally.

When I was a child, she was diagnosed with lymphoma, the very type of cancer that she’d spent her career studying. She passed away in 2016. Her legacy is a huge part of why I care so deeply about genetics, not just as a science, but as a tool to bring understanding, connection, and healing to families.

How does your passion play out on campus?

As a board member for Tufts Hillel, I introduced Gift of Life as a volunteer project, and am now their official representative at Tufts. The organization focuses on blood cancers and other blood disorders, which can be cured through bone marrow or blood stem-cell transplants. Essentially, a donor can help save someone’s life.

Many people can find stem-cell matches in their family. If you can’t find someone in your family, you have to find someone who happens to have a similar genetic background. We try to fill the gaps by swabbing the cheeks of as many people as possible.

I made a “Gift of Life Tufts” Instagram account, sent messages to every Tufts club I could find, and heard back from several. Given the challenges in finding matches for mixed-race patients, I also reached out to the Tufts Association of Mixed People. Within hours, we were planning our first drive at the Mayer Campus Center. That November, we swabbed nearly 100 students, many of mixed backgrounds.

What’s the impact of your work?

Not only are we getting swabs, we’re educating people on how they can save lives. Three Tufts students have been identified as matches for patients battling acute myelogenous leukemia—a 75-year-old woman, a 55-year-old woman, and a 19-year-old boy. My best friend and roommate is his match!

If a match goes through with a donation, they’re able to meet in person. I’ve attended two Gift of Life events where donors meet their recipients for the first time. Everyone was crying. It’s such an emotional event.

How will your passion make a difference on campus and beyond?

I want to market Gift of Life to more people on campus. You can save a life, which is something that I don’t think a lot of people can say.

I’m also a research intern at The Doan Lab at Boston Children’s Hospital, in the Department of Genetics and Genomics, which is working to improve the understanding of the genetic underpinning of primary ADHD.

I hope to pursue a career as a health psychologist. I hope to support children and families impacted by rare genetic disorders, because there’s so little discussion about them. I’m already starting to do this while working with a local three-year-old boy with a rare genetic disorder, ZTTK syndrome.

I also want to help shift the way people think about genetics. So often, genetics is associated with things like designer babies or science fiction. But by understanding genetics, we’re able to develop treatments for diseases such as cancer and ALS.

I believe genetics is the future of science. If we can truly understand genetics, we can understand medical mysteries and give answers to families who’ve been searching for years.

Latest Tufts Now

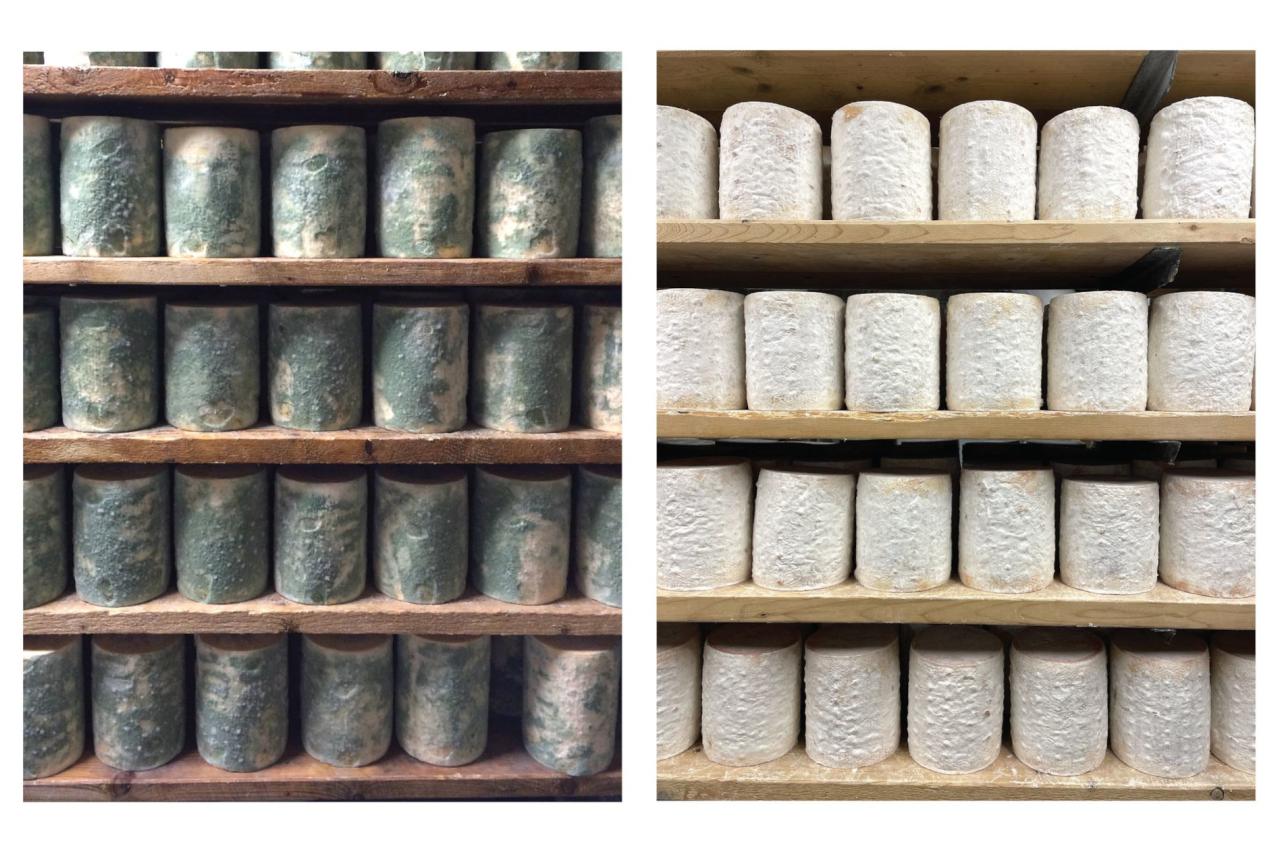

- Cheese Fungi Help Unlock Secrets of EvolutionColor changes in fungi on cheese rinds point to specific molecular mechanisms of genetic adaptation—and sometimes a tastier cheese

- What’s the Federal Reserve and Why Is Its Independence Important?As the president tries to take control of the nation’s central bank, an economist explains the dangers for the economy

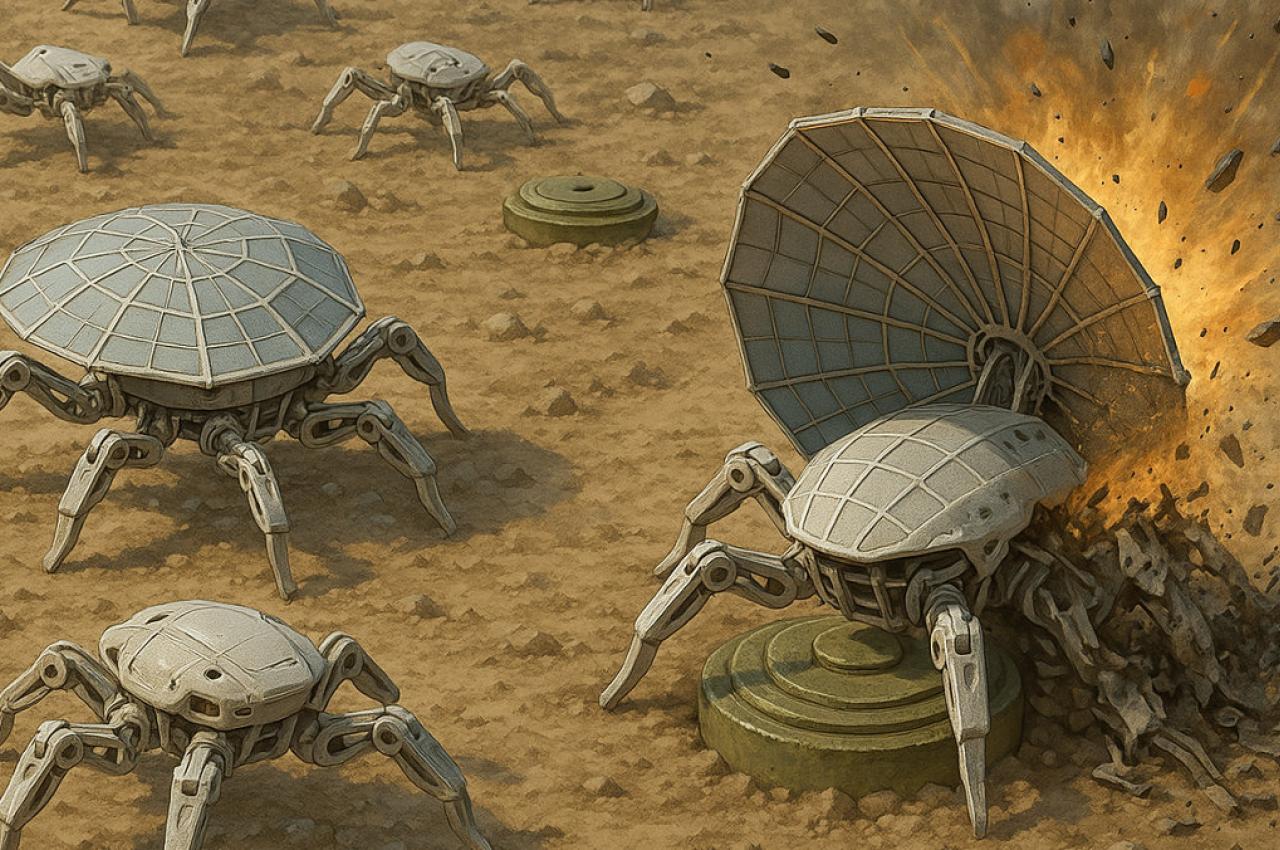

- Crab-Inspired Robot Development Moves Forward with New GrantMulti-legged robots could be manufactured at low cost, capable of learning on land and underwater for tasks such as landmine clearance

- Tufts Launches University-Wide Training Series on Civil Rights ProtectionsNearly 100 sessions will be made available to accommodate all faculty, staff, and affiliates at the university

- Tufts’ Fulbright Fellows Embark on Global Journeys of DiscoveryEight Tufts alumni participating in the Fulbright U.S. Student program reflect on what they hope to learn from working and living outside of their home country

- Tufts Will Be Tuition-Free for U.S. Families Earning Less Than $150,000With the Tufts Tuition Pact, the university underlines its commitment to reducing financial barriers for its undergraduates