For Real Talk About Public Education, Check Out This Fictional School

Public school is the setting for countless coming-of-age tales—but how realistic are those media portrayals? We turned to two experts: Shameka Powell, an associate professor in Tufts University’s Department of Education focusing on educational equity, and developmental psychologist Erin Seaton, who lectures in the Department of Education and is co-director of the school psychology program.

Powell and Seaton say that the media usually rely on two tropes: wealthy suburban schools or chaotic urban ones. But they agree that ABC’s Abbott Elementary broke the mold. The Emmy- and Golden Globe Award-winning show, now in its fifth season, spotlights a primarily Black, underfunded Philadelphia school with nuanced characters facing real-world challenges, without tidy endings or cliched plot-lines.

“Abbott Elementary is a breath of fresh air. It portrays a public school that centers Black and brown youth and approaches it from an asset perspective versus a deficit perspective,” Powell says.

Powell and Seaton share what we can learn about modern classrooms from this approach.

How has public education traditionally been portrayed in the media?

Powell: When we think about how public schooling has been portrayed in popular media, it’s one of two ways: Boy Meets World or Saved By the Bell are very whitewashed portrayals of public schooling.

When you think about how race and particularly kids of color intersect with public schooling, it’s from a deficit perspective. Think about Freedom Writers: There’s one white woman teacher who’s going to save all of the students of color. Think about Lean on Me: You have a Black male principal who’s authoritarian, to say the least. He’s there to tame these kids of color. They actually play the song “Welcome to the Jungle.”

It suggests that kids of color in general and Black students specifically are culturally deficient, that there’s a pathology that exists within Black culture that the school has to separate the Black students from. Or else, the school has to suggest to students that their culture has nothing to offer, that their culture is the problem.

Seaton: There’s a very stereotypical middle-class experience of education that shows well-resourced districts, or there’s the under-resourced, urban school. An example might include Real Women Have Curves, Stand And Deliver, or Lean on Me, portraying urban schools from a white lens as being not only underfunded and struggling, but through a very racialized lens. These are portrayals of schools in a racialized context as jungles, just completely out of control, as though one teacher can act as a savior for children.

Why is Abbott Elementary different?

Seaton: The really beautiful thing about Abbott is that we see a different lens. We see teachers who are struggling and passionate. There’s certainly tension between district administrators and the school, but it’s much more of an on-the-ground, realistic portrayal of the interactions between teachers and students. It’s not a one-sided look at schools. There are really beautiful moments that are unexpected in terms of media portrayals, where parents are really trying to engage—even parents who are judged or stereotyped by teachers. We see a side where they’re trying very hard. There’s a lot of moments in Abbott with family-school collaboration, just tiny little snippets, where parents are trying to build a system of support around a child.

Powell: It’s a portrayal of public schools that are giving back and of teachers who are competent. It seems like such a low bar. It also complicates the narrative by saying, “Even as teachers are doing these great things, and even as teachers are putting one foot in front of the other to meet the needs of the students, teachers are not saviors.” There are structural factors that constrain and create the conditions that teachers and students are engaging with.

Abbott talks a lot about the district not giving funding, and that’s a reality. It focuses our attention on how broader structures, whether that’s the school district or the city, have a responsibility to the public. Because they do not uphold that responsibility, teachers and students have to bear the brunt of it.

Why is there a dissonance between between how a public school might operate versus how it’s portrayed in the media?

Powell: Production companies want to make money, and it’s easy to tell a narrative that’s been told. It’s easier to do that than to provide a narrative that challenges schemas that have been constructed. It fits into a schema that we have constructed about public schooling, specifically public schools that teach Black and brown youth.

Another reason is our dis-investment in anything public, whether that’s public transportation, public services, public utilities. The public is seen as a space of rapacious mooching off the system. The public is seen as a space bereft of anything to offer; it only takes. What that then means is those in power don’t have a responsibility to support the public, whether that’s public transportation, utilities, schooling, and so forth. Movies and TV shows parrot that incorrect understanding. Abbott is a palate cleanser in many regards.

What would you like viewers to think about when consuming this kind of media?

Powell: I want them to know that schools cannot solve America’s social ills. Schools are spaces that can help address inequalities, but schools are not a silver bullet. We do ourselves a disservice if we portray schools as the answer, because that means, if schools are the answer to the problems, the problems can be addressed simply by learning things. We know that not to be the case. There has to be a multi-pronged approach to addressing social inequality.

When we think about the most pressing issues confronting public education today, what are they? What worries you? What do you want people to learn more about?

Powell: Schools are one of the last bastions of democratic good. One worry for me with schooling, other than not providing adequate equitable resources, is making education nothing more than testing and meeting benchmarks in order to go to the next grade, to go to college, and to get a good job—schooling being a means to an end versus recognizing that schools are where education can happen. We are building a citizenry here. These students and teachers are not empty vessels. They have experiences. They navigate numerous worlds.

Seaton: There’s an overwhelming mental health crisis. And, as a country, we’re at a critical turning point in which students cannot come to school and feel safe in their identity. The stripping away of protections for students makes it almost impossible for teachers, school psychologists, and counselors to engage in ethical practices and serve their students in certain states.

The underfunding of education is not new. I have students who are in districts that have a recording studio in their building, six school psychologists, and outdoor spaces for young children to play. And I have students where a school psychologist is serving three schools and doesn’t have an office. Those systemic inequalities continue to be so present in the way that education is segregated.

What can we do about school inequality?

Powell: My first answer will always be to redistribute resources. We can change the funding schemes. Schools are often funded by property taxes. What would it look like to instead ask: What do the students at this school need? How can we provide that? A student-first approach might be one thing, and understanding that the student is not just an individual; the student represents a community, a family, a location. The student exists in the broader ecosystem, and we do a disservice if we say we want students to succeed but don’t provide them the resources needed to do so.

Seaton: [Offer] a sustainable salary for teachers. Actually compensate teachers for the work teachers are doing. I think Abbott does a great job showing how teachers are not paid for the work that they do. They spend time and resources beyond the school day, and they don’t have time to do everything that they need to do. There are so many resources in our country that are put into places other than education, and if we could just pour them into education, that would be one step in funding counselors, school psychologists, and guidance counselors.

When students apply to college, they sometimes have one guidance counselor for 1,200 students. In private schools, you have one guidance counselor who has six students per caseload. When you’re applying to college, and you’re getting recommendations from a guidance counselor, it may be somebody who knows you, or it may be somebody you’ve never met. Those inequalities carry into higher education.

How have school portrayals changed since the ’80s and ’90s, when some of those classic films came out? How have the challenges of teaching changed?

Seaton: My kids have trouble watching shows that were made in the ’80s, ’90s, or even the early 2000s, because they feel so dated. The technology is so dated. They live in a context where students need to feel connected all the time. Some shows are just irrelevant. Those aren’t the pressures they’re feeling. We have such a broader understanding of the importance of identity in education that’s just underrepresented in books and media, and has really shifted.

Abbott has an out gay teacher. In the ’80s, that would not have happened on a TV show about an elementary school in the same way. Race, class, gender, sexuality, or religion are all meaningful aspects of the complex identities we bring to school. Unlike past shows about education that showcase these topics, Abbott has a beautiful way of showing that this is just part of going to school; these are things that we just encounter as part of the school experience.

Latest Tufts Now

- When an Old Flag Isn’t So GrandMany states are redesigning their flags. Will it change how people feel about their home states?

- Uncovering the Biology of Growing OldLarge study in pet dogs uncovers potential new biomarkers of aging that may one day help them—and humans—live longer, healthier lives

- Can AI Be Conscious?Experts debate the possibility at a symposium in honor of Daniel Dennett, and most agree it’s not a good thing

- Tufts Veterinarian Helps Produce First Purebred Herdwick Sheep Born in U.S.Years of planning, precision timing, and the persistence of a local farmer culminated in the birth of 11 lambs this summer

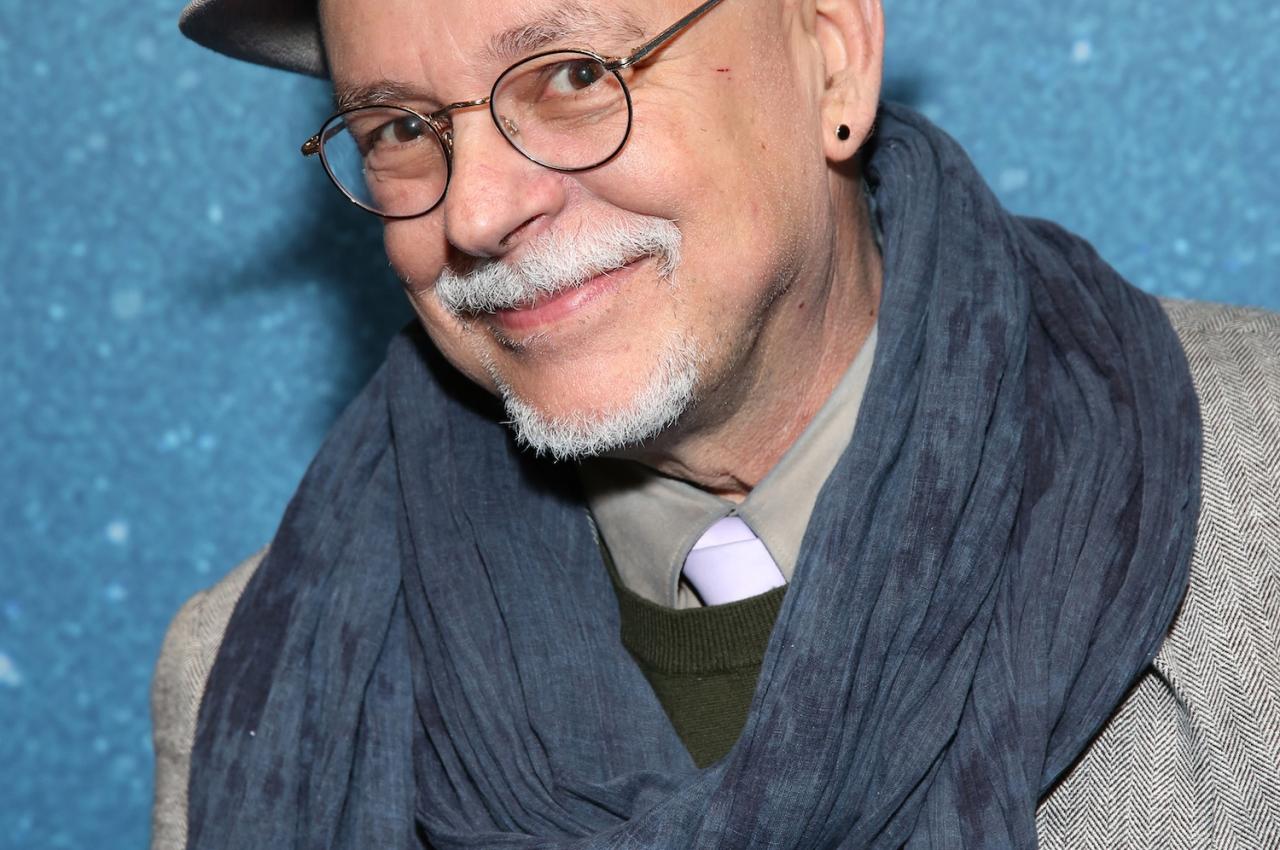

- The Wizard Behind WickedHow Gregory Maguire, AG90, created the story that inspired the blockbuster musical and movies

- What Happens When Neighborhood Pharmacies CloseSchool of Medicine experts explain pharmacy deserts and how consumers are impacted by thousands of shuttered drugstore locations