When Two (Identical) Heads Are Better Than One

To say that sisters Hannah and Madeline Rieders are similar would be an understatement. They are both students in the Master of Public Health (MPH) program at Tufts University School of Medicine. They were both competitive distance runners as undergraduates at Mount Holyoke College and continue to run for fun. They each earned a master of science degree in environmental justice from the University of Michigan. They share an apartment, and they even share a birthday.

“For the most part, we have similar class schedules and work habits, and do pretty much everything together,” said Hannah, who is one minute older than Madeline.

These identical twins, who expect to finish the program in December, are both public health researchers who have co-authored six published manuscripts so far. Armed with the sense of commitment that fueled their athletic and academic endeavors to date, they’re leaning into their special brand of teamwork to cope with the challenging aspects of their program and deepen their investigation of public health threats, such as air pollution.

Their classmates and professors often have trouble telling them apart at first. But after getting to know them, people can usually distinguish one from the other by slight differences. For example, Madeline is a little taller.

“I feel like our brains click together. We’ve always been very collaborative,” said Madeline. “A huge bonus of being twins is that we work so well together. That has fed into our competitive sports and academic careers, and now we’re working together in research.”

Hannah and Madeline Rieders were both competitive distance runners who continue to run for fun. Photo: Courtesy of the Rieders Family

Research All-Stars

Their most recent paper, published in the journal Local Environment, examined how air pollution and social factors help explain why people in redlined neighborhoods have shorter life expectancies. A redlined neighborhood is an area that historically was denied financial services and resources, often due to racial discrimination, which has had lasting consequences in the form of persistent economic inequalities.

Environmental epidemiologist Laura Corlin, A13, EG15, EG18, associate professor in the Department of Public Health and Community Medicine at the School of Medicine, was their faculty mentor for the project.

“This is a technically complex paper, and these phenomenal master’s students took it by storm,” said Corlin. “They learned a ton that went well beyond what they were doing in their coursework and were very efficient at getting this paper published in a journal.”

But it was Michael Siegel, professor of public health and community medicine at the School of Medicine, who encouraged their early research interests—even before they arrived at Tufts.

Hannah and MadeIine first met Siegel during the COVID-19 pandemic, when they were undergrads and living at home in a suburb outside of Boston. The twins were injured from running—with different injuries—and were cross-training in a local pool for rehabilitation. Coincidentally, Siegel frequently swims at the same pool. One day they struck up a conversation about his work, and he offered them an opportunity to help with his research.

“After talking to Dr. Siegel, we realized the interconnection between environmental justice and public health issues. At that point, we were just planning on helping with his research that aligned with environmental justice,” said Madeline.

But at UMichigan, they refined their interests in examining how environmental and structural factors contribute to racial health disparities and decided to pursue an MPH degree.

The twins share an apartment in Boston and say they’re fortunate to have someone to provide a deep level of support. Photo: Courtesy of the Rieders Family

The sisters were selected as the first recipients of the Ruth Wilner Siegel Memorial Student Research Fund, a fellowship program that Siegel set up in his mother’s memory. As Siegel Fellows, they’ve been conducting research since fall 2024 under the mentorship of Siegel, Corlin, and Professor Thomas Stopka.

“From the moment I met them, it was clear both Hannah and Madeline were all-stars,” said Siegel. “I guess it wasn’t below me to be recruiting at a swimming pool in the summer, but Tufts—and the public health community—has reaped the rewards of bringing these amazing young women into the field of public health and environmental justice.”

With Siegel, they co-authored multiple papers on structural racism and racial disparities including papers in October 2023, July 2023, June 2023, and December 2022.

On the first few papers with Siegel, they learned how to collect, analyze, and clean research data, as well as how to write a manuscript. “For our most recent paper on air pollution, we initiated and developed the whole project as co-first authors. Because we were spearheading, we had to figure out the methods to use and how to write it in the best way,” said Madeline.

They employed Geographic Information System (GIS) mapping and different types of statistical analyses such as structural equation modeling to examine the role of particulate matter and social determinants of health in the relationship between historic redlining and modern-day life expectancy. They cited the course Intermediate Biostatistics: Regression Methods as being especially helpful.

“Madeline and Hannah adroitly parlayed their experience from our GIS/Spatial Epidemiology MPH course into applied development of outstanding descriptive maps and the spatial analytics needed to depict communities that continue to be impacted by the detrimental legacy of redlining and correlations with salient health outcomes,” said Stopka.

Sister Support System

Whether in coursework or research, Hannah and Madeline said they try to help each other out through challenges in their work. They acknowledge that they’re fortunate to have someone with whom to troubleshoot problems and provide a deep level of support.

Hannah is one minute older than Madeline. Now that they're grown, Madeline is a little bit taller than Hannah. Photo: Courtesy of the Rieders Family

“It’s hard to work with another student who doesn’t necessarily think like you do. You can’t usually both work on the same part of a project; you have to delegate it. But somehow, we’re able to work together on the whole project at the same time,” said Hannah. “It helps us catch each other’s mistakes and gives us two perspectives at once. It’s nice to have someone in the program to help navigate those challenges. It’s like a built-in study buddy.”

They’re currently working on their applied practice experience (APE), which is similar to an internship and required by the program, at the Cambridge Public Health Department.

In the future, they insist they wouldn’t necessarily need to find a job together, as that could limit the opportunities, though they agreed it would be a bonus. With their passion for environmental health, they’re both interested in public health research or working at a local public health department.

“I was continuously amazed at the complementary skills and the can-do attitude of these twin sisters. Upon receiving feedback and recommendations during meetings, Hannah and Madeline would respond, completing one another's sentences, riffing off one another, and arriving at a solid plan for next steps,” said Stopka. “They are a dynamic duo!”

Adapt and Stay Flexible

Hannah and Madeline did not expect to go back to school for a second master’s degree after earning their first one. But Hannah said it’s important for students to be adaptable and flexible, and to let their interests drive them.

“Undergraduates need to be open minded, because you don’t know where your academic and career path are going to take you. Plans change,” said Hannah.

They’re appreciative of the guidance, support, and responsiveness of faculty at the School of Medicine and said they’ve felt like the school prioritizes students’ needs.

“Five years ago, I had no idea what I wanted to do with my environmental studies degree,” Madeline recalled. “You don’t have to necessarily know what you want to do before college. But through Tufts, I’ve gained further refinement and understanding of my path.”

Latest Tufts Now

- Matriculation Week 2025From move-in and Pre-O to Matriculation, the Class of 2029 had a warm welcome to campus

- Julia Cavallaro’s Inspired Take on Early MusicThe graduate student in music composition brings nuanced interpretations to works from centuries past

- Student-Designed Wind Tunnel Passes the TestCapable of reaching speeds of up to 380 miles per hour, the device will expand research on optimal aerodynamics

- A Tufts-Led, Historic Commitment to SustainabilityThirty-five years ago, Tufts guided other universities to the creation of the Talloires Declaration. Its legacy endures today

- How Rural Women Advance India’s Sustainable FutureAjaita Shah’s innovative “tech + trust” model has built a network of women entrepreneurs

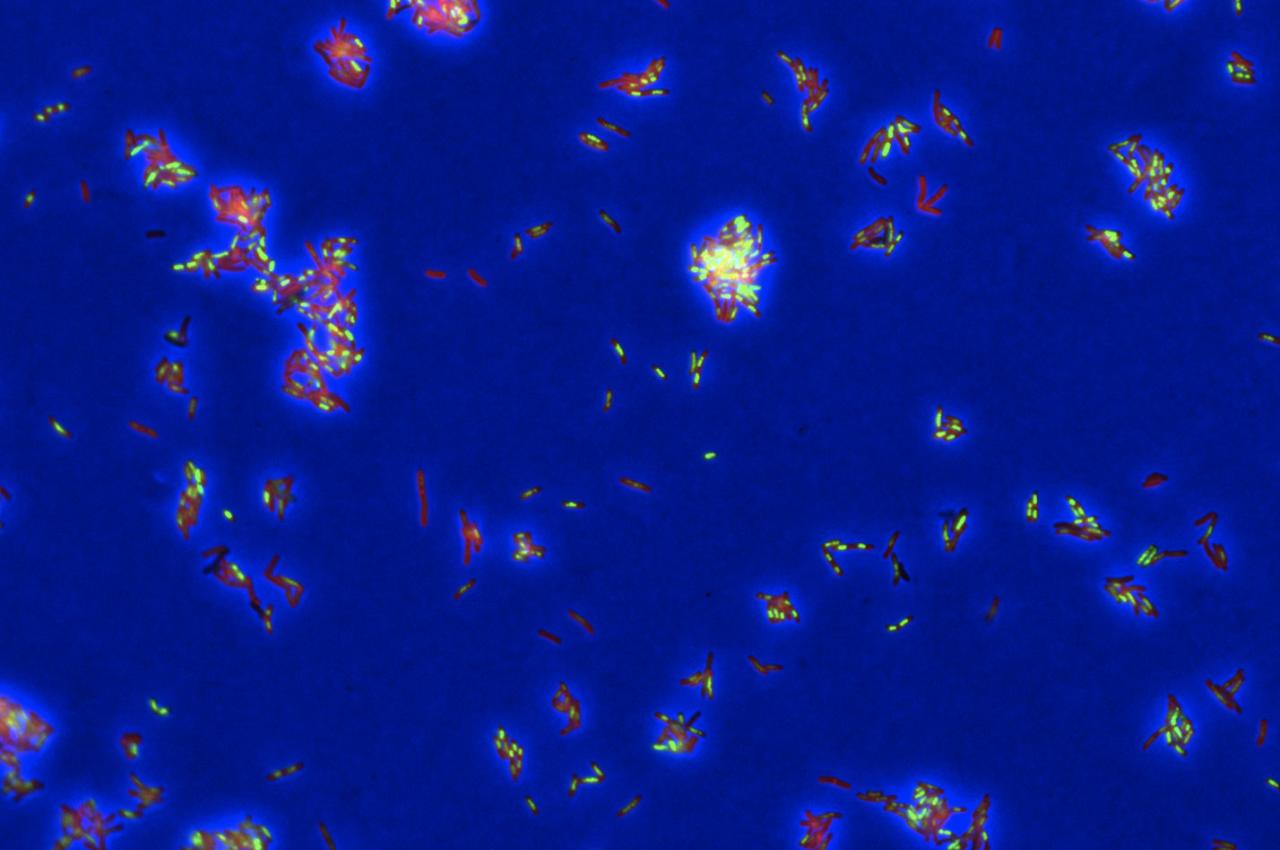

- New AI Tool Reveals How Drugs Kill TuberculosisTufts researchers’ approach uncovers how TB treatments can best work together at the cellular level to speed better cures