I Protected My Children from Our Holocaust History. But Then They Grew Up

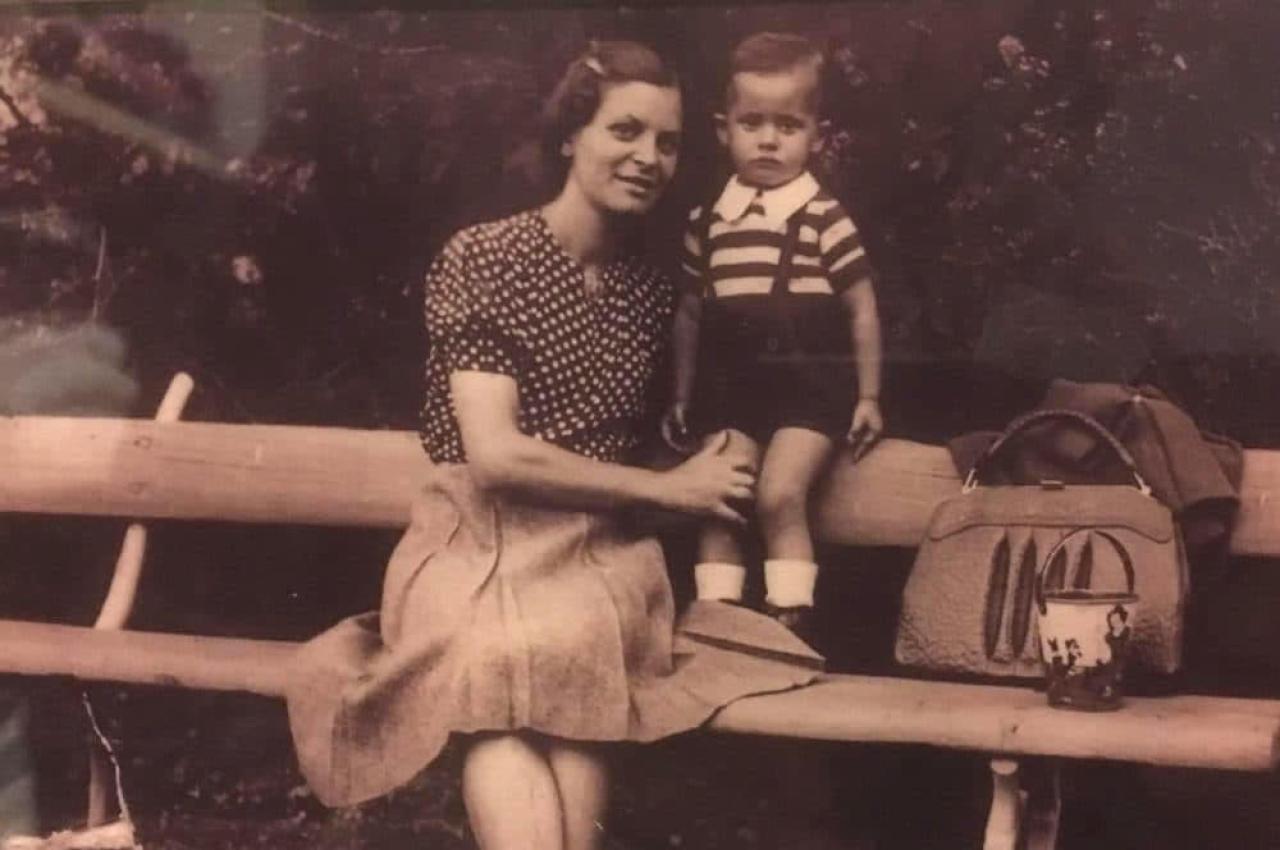

My father’s vivid stories and our bond made it easy for me, an American child, to see him as a small, dark-haired boy peeking out his front window when his mother wasn’t looking, curious to see the German soldiers patrolling his Jewish neighborhood.

His earliest memory was of the surprise Nazi bombing of Belgrade, Yugoslavia; he was not quite 3, too young to remember the destruction of his city. Instead, he recalled his fascination with a plate of cookies knocked off a wardrobe by relentless explosions. It somehow split neatly in two instead of shattering. As a little girl, I could see the clean break, the two pieces of china on the floor and the treats scattered about.

When my father recounted riding on his teenage cousin’s shoulders as his family followed the railroad tracks out of the bombed-out city, I imagined looking down on the heads of hundreds of people making their way to the relative safety of the countryside. My father’s memories played like cinematic shorts in my mind.

The Holocaust was a generation before my birth and a continent away. Yet, as a child, I wondered which gentile neighbors might hide me, like Anne Frank, in a secret attic.

When I gave birth in my 20s, I was hit by how vulnerable parenthood is. Literally and figuratively, I could no longer run for my life. Babies can’t be kept quiet for hours. Toddlers can’t keep up and are too heavy to carry for miles. Children are so fragile.

As a young mother, instead of identifying with the “I” in my father’s stories, the little boy with his child’s limited perspective on the war he was living through, I thought about my grandparents. How sick with worry for my father they must have been.

My grandfather didn’t run with false papers like his brothers who survived. He hesitated, perhaps because unlike his siblings, he had a wife and young son. Then the Germans trapped him in their net. Horrifically, after my grandfather endured seven months of slave labor, soldiers murdered him by firing squad. I knew my father survived in the countryside with his mother, but I didn’t fully understand how.

The grand Hotel Moskva, where Julie Brill and her family stayed during a 2017 visit to Belgrade, was commandeered by the Gestapo for their headquarters in World War II. Photo: Courtesy of Julie Brill

My plan was to protect my two daughters from this dreadful family history for as long as possible. What was important was not just that they be safe, but that they feel safe. We read books about secret gardens, life on the American prairie, and spiders who can talk and spell. The Devil’s Arithmetic, Number the Stars, and The Diary of a Young Girl could wait.

But children grow up, of course. The sleeves I folded back twice to keep out of the charoset at Passover barely reached my daughter’s wrist bone when I took the dress out of the closet again at Yom Kippur. One year, summer ended, and she didn’t need new shoes because the ones from last year still fit.

Suddenly, I was no longer the tallest person in my home. Next, one of my babies backed her Toyota out of the driveway, the rear seat piled high with boxes and bedding, headed for another year of dorm life. She didn’t need my help to move in.

My quiet, empty nest came with the time to investigate family history and learn the story of the Holocaust in Serbia. I needed to make my father’s childhood stories make sense. Research led to plans for a trip to Belgrade with my father. When my 21-year-old daughter Rebecca heard about our intention, she wanted to come.

Sometimes in the fog of parenting, showing how to zip a jacket or cook oatmeal, I’d lost sight of the actual map. We are teaching our children the pieces they need to be independent adults who can stand tall, make decisions, and care for themselves. And this is the view I catch of my daughter on the street in Belgrade: a college student on the brink of making her own way in the world.

Julie Brill’s father, Haim, and her daughter Rebecca visited Belgrade with her in 2017. Photo: Courtesy of Julie Brill

We are back to see where our family is from, where my father lived until he was 10 years old, and where my grandfather and most of Belgrade’s Jews were murdered.

We are staying in the Hotel Moskva, a grand European hotel in the city center. During the occupation, the Gestapo commandeered it for their headquarters. I can’t decide if my choice of accommodations is a triumph over the past or somehow a failure to honor it.

On our first morning, we pause on the sidewalk outside our hotel. My father recounts watching the diners in the outside café here 70 years before, when he was a skinny, fatherless kid with empty pockets. I observe Rebecca capturing the moment on her iPhone. Her long, dark hair is pulled up in a ponytail in anticipation of the heat that will come. She is ready for the stories, the emotion, and the heartbreak the day will bring.

None of us are born into a shiny, new world. Our stories start long before we arrive. They form us. When we explain our history to our children, we help them to understand themselves.

My beautiful daughter will have stories to share one day, perhaps with her children, grandchildren, nieces, and nephews. She is preserving our legacy not just on her phone, but in her memory.

Julie Brill is the author of Hidden in Plain Sight: A Family Memoir and the Untold Story of the Holocaust in Serbia.

Latest Tufts Now

- New Approach to Alternative Energy Sources for College CampusesAt Tufts, state officials, higher education representatives, and energy experts highlight new regulations that could improve access to geothermal energy and lower costs for all

- In Alaska, an Engineering Student Unlocks the Power of StoriesHaniye Safarpour listens when people talk about life with, and without, water

- The Unending War in UkraineDespite more than three years of brutal conflict, Ukrainians are still mostly unified in fighting off Russian invaders, says political scientist

- Seed Oils Aren’t the Problem—How We Consume Them IsNutrition experts separate fact from fiction on plant-based oils, also known as seed oils, what products to choose, and why you might pick oil over butter or tallow

- What Mamdani’s Victory Says About Engaging Gen Z VotersHis campaign drew a surge of new voters, including young people. Will the youth vote help shape the 2026 midterms, too?

- TB Bacteria Play Possum to Evade VaccinesGenetic study reveals how Mycobacterium tuberculosis survives in vaccinated or previously infected hosts