Succession Battles Are Not Just a TV Trope

Running successful family-owned businesses can be tricky. There’s usually a strong-willed founder who keeps tight control of the business, and there are often succession issues: Who in the family is able and willing to take over when the founder retires?

You can see that on TV—think of the popular show Succession—and in real life, especially now in New England, where conflict in the family that owns large and successful grocery chain Market Basket is now back on the front pages.

Market Basket made national news in 2014, when conflict between two feuding cousins—sons of the co-founders—led the board of directors who favored Arthur S. Demoulas to fire CEO Arthur T. Demoulas. The move brought the popular chain to its feet, as employees and customers loyal to Arthur T. boycotted the stores. Arthur T. and his allies—three of his sisters—eventually bought out Arthur S. and other family members, and the company continued to grow, with annual sales now topping $7 billion.

But last month, the company board, allied with the sisters, put CEO Arthur T. Demoulas on leave, accusing him and company management of ignoring the board’s directives and questions concerning succession issues.

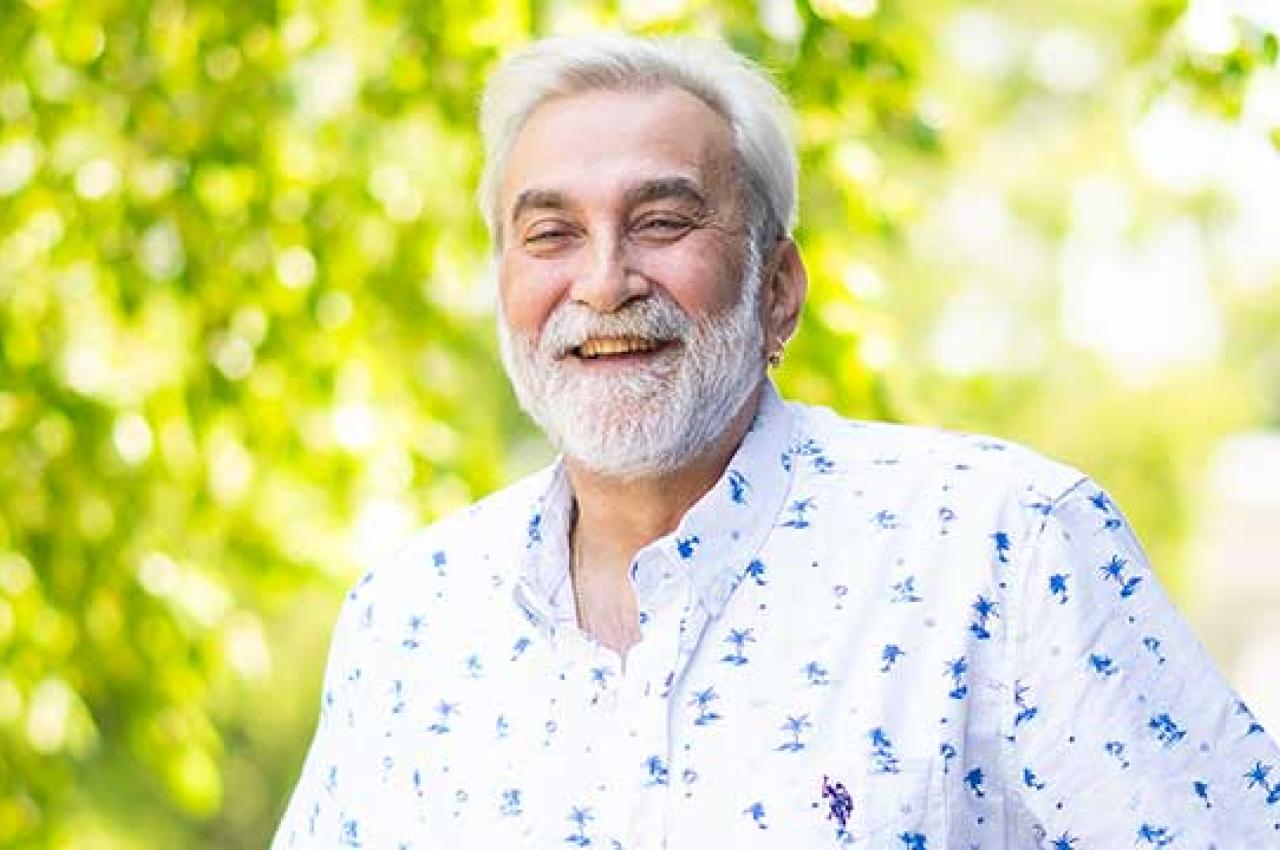

“There are traps that happen with family businesses that cause them to derail, and I think Market Basket fell into one of those traps,” says Frank Apeseche, a professor of the practice at the Gordon Institute at Tufts. He teaches business strategy, finance, and enterprise management, and knows about family-owned businesses from his roles as an unrelated insider—he was brought in to be CEO of the family-owned Berkshire Group for a dozen years, and is currently chair of another family-owned organization.

“Most of the time, conflict deals with skillsets—family members not having the right skills for the job,” he says. “I think Market Basket has the right skillset, but they don’t have good governance.”

Traditionally, the founder of a large, successful family-owned business “is a patriarch, or less frequently matriarch, who is really good at starting something up, is super creative, usually extraordinarily charismatic—very, very powerful,” Apeseche says. “But it takes a different personality to scale it up. Often founders just assume that their children can do what they do—and it’s highly unlikely that anyone can do what they do.”

Smart founders, he adds, “are thinking ahead and are really interested in succession planning, usually bringing in outside experts who have experience to help set up an infrastructure and then probably be part of that infrastructure.”

It’s About Good Governance—and Personality

Typical family business challenges center on the skillsets and mindsets—can they do the work? do they have the drive to do it?—of the second or third generation, says Apeseche. “Do they want to work the 80 hours a week, go through the grind, have to deal with a multitude of balls in the air, and be extraordinarily diplomatic?”

Successors also have to deal with the founder. “That’s the extra challenge, because most of the time, a very powerful, very controlling patriarch or matriarch keeps challenging them and doesn’t give them enough space to grow,” he says.

A way to avoid family disputes is through good corporate governance, Apeseche says. That means having a board of directors for the business, usually with outside directors and a clear division of roles. “In the case of Market Basket, governance was apparently never really agreed upon,” he says.

Arthur T. Demoulas, who was first appointed CEO in 2008, “is talented, knows the operations, and successfully grew the business. He probably was saying to himself that he was doing all the work, and deserved to take control,” Apeseche says. “But governance was not set up, not agreed on—and there are certainly other family businesses just like that.”

Apeseche says that well-run family-owned businesses rest on what he calls four pillars of success. Family members running the business “need the skillset to do the work, the mindset to be fully engaged in the demands of the work, a personal agenda that conforms to the mission of the business, and the political dexterity to deal with people inside and outside of the company,” he says.

“I think with Market Basket, first the personal agendas are off—the individuals are not putting the business interest first. Second, the political dexterity is missing,” he says.

“When I was the CEO of a family-owned business, I think my special talent was that I had good political dexterity,” he says. “I could read the room, I could understand all the family members, I could pick up what they weren’t talking about, but what they were very much feeling. And I was good at managing multiple stakeholders simultaneously while keeping the business moving forward. But that’s not a skill everyone has.”

Some family businesses bring in outsiders like Apeseche to run things, and some founders hire outsiders to help mentor their children to become successors. One way to do that, he says, is to bring children into the business, but not start them at the top.

“Bring them in at a role that they can be successful at,” he says. “This is what founder Ned Johnson did with current CEO Abigail Johnson at Fidelity Investments—brought her into a number of different roles to learn more of the business and then slowly elevated her.”

Market Basket isn’t alone in its troubles, Apeseche says. Governance is generally difficult with family-owned businesses. Even having an agreed upon business governance and succession plan doesn’t always work.

“The planning is super complicated, and then when you actually have to implement it, it’s all about relinquishing appropriate control at the right time,” he says. “Many times I faced patriarchs who basically said, no, I won’t do that. All of a sudden behind the scenes, they had changed their minds.”

Getting a family-owned business to work well “is hard,” he says. “It’s really hard.”

Latest Tufts Now

- Cells Have a Second DNA Repair Toolbox for Difficult CasesCancer cells may rely heavily on backup mechanisms of DNA repair, presenting a vulnerability for targeted treatments

- Putting Science at the Forefront for the Next GenerationArea high school students learn biomedical engineering by working with graduate students and faculty in Tufts labs in a free summer program

- The Gulf of Maine Is Warming Faster Than Pretty Much Anywhere ElseThese researchers are hurrying to help coastline communities and economies adapt to the changing waters

- Am I Getting Enough B Vitamins?Make sure to take in the right amount, but not too much, of these eight key nutrients, according to a Tufts nutrition expert

- ‘I Never Looked Down on Any Job I Had’A carpenter and longtime member of the Tufts Facilities team on taking pride in one’s work

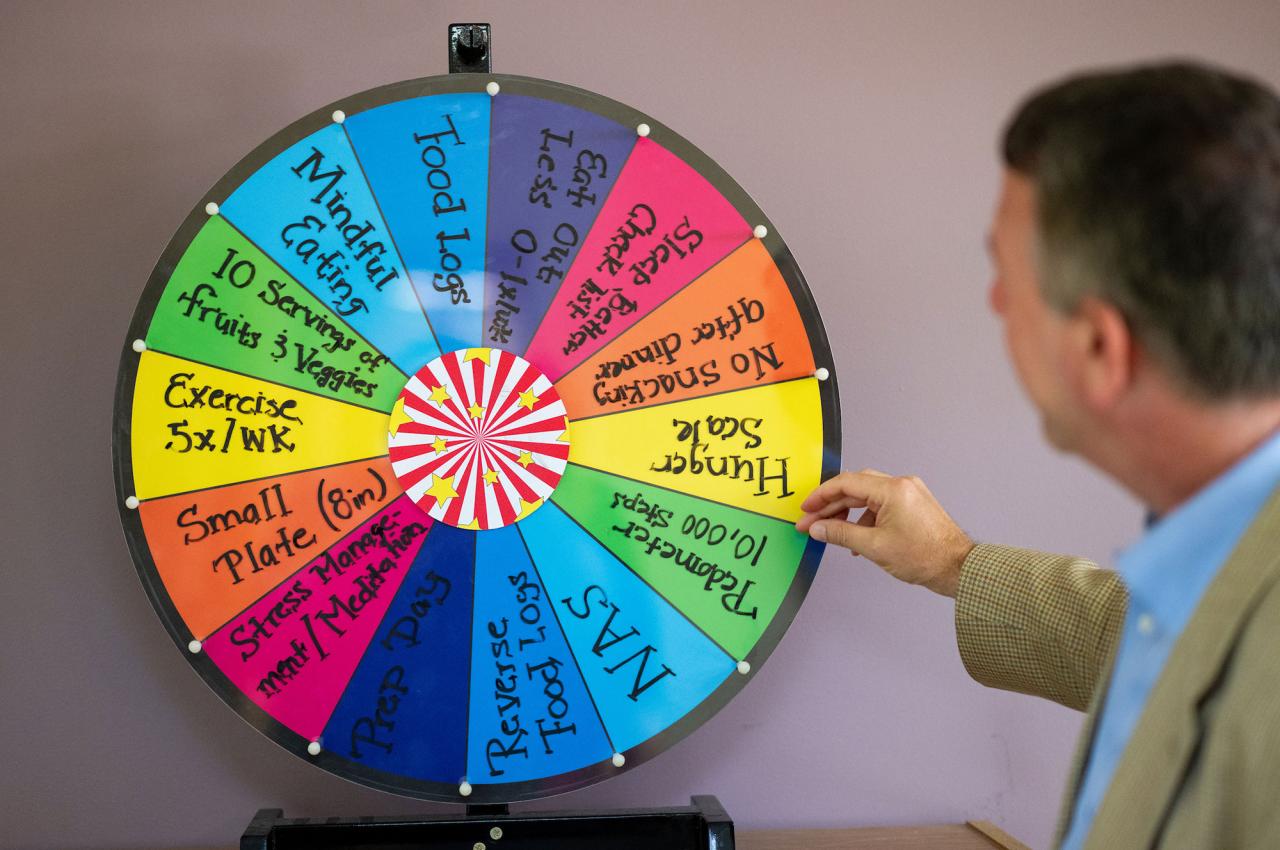

- For Some, ‘Group Magic’ Is the Key to WellnessHere's what happened when a family medicine physician and a dietitian teamed up to help groups of participants develop better health habits for life