Tufts Veterinarian Helps Produce First Purebred Herdwick Sheep Born in U.S.

Rachael Gately, D.V.M., spends hundreds of hours a year getting up close and personal with livestock. An associate clinical professor at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University, Gately is part of the Tufts Veterinary Field Service (TVFS) and focuses on theriogenology, or animal reproduction, using assisted reproductive techniques (ART) to help farmers manage their animals.

“I artificially inseminate more than a thousand animals each year. In the fall and winter, it’s sheep and goat season, and in the spring and summer, it’s horses. Cattle are all year long. My whole life is ART,” Gately said with a smile.

Gately’s interest in sheep, in particular, is both professional and personal. She grew up on her grandparents’ farm in northern Connecticut and has raised nationally competitive breeding sheep for over 25 years. She now lives on that same farm where she keeps about 75 Texel and Polled Dorset sheep.

One of her clients is Judith Hooper, Ph.D., owner of Grass Hill Farm, which is nestled in the hills of northeast Connecticut, also known as the Quiet Corner. Hooper is one of only a handful of people in the country who keeps a flock of Herdwick sheep—a specialty breed from the U.K. It’s a second career for Hooper, who retired as a scientist focusing on agriculture and nutrition in Arizona and returned to the area where she grew up.

Until recently, a purebred Herdwick sheep had never been born in the U.S. But thanks to Gately’s rare skillset and Hooper’s determined persistence, for the first time, purebred Herdwick lambs were born on this side of the Atlantic in June. The event, which took years of planning, required a little luck, a lot of patience—and precision timing.

Meet the Sheep

Herdwick sheep are a hill breed that roam the rocky cliffs of Scotland and England. They’re prized for their thick fleece and are known to be calm, sturdy, intelligent, and robust enough to withstand cold winters. Importing sheep and other livestock from foreign countries is highly restricted in the U.S. to prevent animal-borne diseases from entering the country. But at times over the years, importing their genetic material—semen and embryos—has been permissible.

In 2008, an Oregon farmer imported the first Herdwick semen into the U.S. and used it to produce lambs that were part Herdwick, but shortly after, regulations changed. It was from that Oregon farm that Hooper sourced her own starter flock of one ram and three ewes in 2013.

“For the next few years, I enjoyed raising lambs,” Hooper said. “But there was no new Herdwick semen on the horizon at that time. My concern about the inevitable inbreeding that would occur in my flock caused me to pause further breeding and focus instead on fiber production.”

The inbreeding was a serious problem. For over a decade, all the Herdwick sheep in the U.S. came from the same genetic source obtained by the Oregon farmer in 2008. “As a result, the sheep’s genetics were becoming tied up in a genetic bottleneck,” said Gately, who completed an internship with TVFS before being hired as faculty.

In 2021, when the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) changed some of the regulations to allow the import of sheep semen and embryos from the U.K with proper screening and testing, Gately and other breeders jumped at the chance to obtain new genetic material.

Meanwhile at Grass Hill Farm, Hooper was working on an upbreeding program. Hooper would obtain new Herdwick sheep semen, and Gately would perform laparoscopic artificial insemination on her ewes. Since the ewes are not Herdwicks, the offspring produced would be 50% Herdwick sheep. The process would continue, next resulting in 75% Herdwick sheep, and eventually 94% Herdwick sheep, but that’s as close to purebred as they can get through this method. In total, the upbreeding cycle typically takes five breeding generations, or 10 years.

Access to embryos from purebred Herdwicks have sped up that process tremendously. It also introduces something that breeding up with semen cannot: maternal genetic influence. To produce a true purebred Herdwick, Hooper needed a fertilized embryo from purebred parents.

Epic Journey for Embryos

By June 2024, Hooper had placed a large order for a variety of embryos from different genetic matings with an importer—Heritage Sheep Reproduction—which has a relationship with a center in the U.K. that collects germplasm for export.

Importing sheep embryos from overseas is hardly a simple undertaking—not to mention the amount of preparation work and care required for the ewes who will receive them. “It's a lot of work, time, and money. It's been a slow process,” said Gately, who is one of only a handful of experts east of the Mississippi River who performs the embryo transfer procedure in small ruminants like sheep and goats.

First, donor sheep in the U.K. go into quarantine to satisfy regulatory requirements for testing and screening. Next, a veterinarian must collect the embryos when they are approximately six days old, which may or may not be successful for a number of reasons, Gately said. Any collected embryos go into a storage tank cooled by liquid nitrogen. The tank is tracked throughout the shipping process, with regular updates automatically messaged to the recipient, as it’s flown to the U.S., where it must clear customs and USDA inspection.

“Last year, I ordered embryos for my own sheep in May, and they were projected to arrive in July, but I finally got them in November,” said Gately. “It was even longer for Judy. After she got the commitment that she would receive embryos, it took 18 months to two years for them to finally get here. The arrival dates just kept getting pushed.”

As they waited for the embryos, Hooper evaluated her ewes to decide which would receive them. The chosen ones would undergo a three-week protocol to regulate their fertility cycles and make sure they’re in the best possible physical condition for insemination. Timing is critical, Gately explains, as sheep have to be at the exact right spot in their cycle for the best chance at conception. If they're not, even if Gately implants the embryo in the correct location in the uterus, the pregnancy will not stick.

“The responsibility is on the owner to do everything right. I give them directions to follow with certain shots and treatments for 21 days leading up to the procedure, and if they skip them, or if they don't take it seriously, it could mean that I'm putting $2,000 worth of embryos into an ewe that may not accept them,” Gately said. “Fortunately, in our case, Judy followed the instructions to a T.”

Throughout the entire process, from preparation through pregnancy and after delivery, the ewes need to be well fed and properly sheared, with their hooves trimmed, body in good condition, and no stress—which can be a tall order. Stress to a sheep could be a rainstorm, Gately added.

The quality of the embryos can also affect the results. Embryos from the U.K. are frozen in glycerol, which protects them in the liquid nitrogen tank. The thawing protocol involves a temperature-controlled water bath followed by moving the embryos through a series of three liquid medias to slowly rehydrate them. The whole process takes about 20 minutes and is done on site right before the procedure. As they thaw, Gately checks the sheep’s ovaries to confirm the ewe is at the correct point in her cycle, and if she’s not, they won’t use that animal as a recipient.

“From the day the embryos were collected in the U.K., they must be handled carefully through the freezing and shipping processes, all the way to the hands of my technician. There are a lot of moving parts,” Gately said.

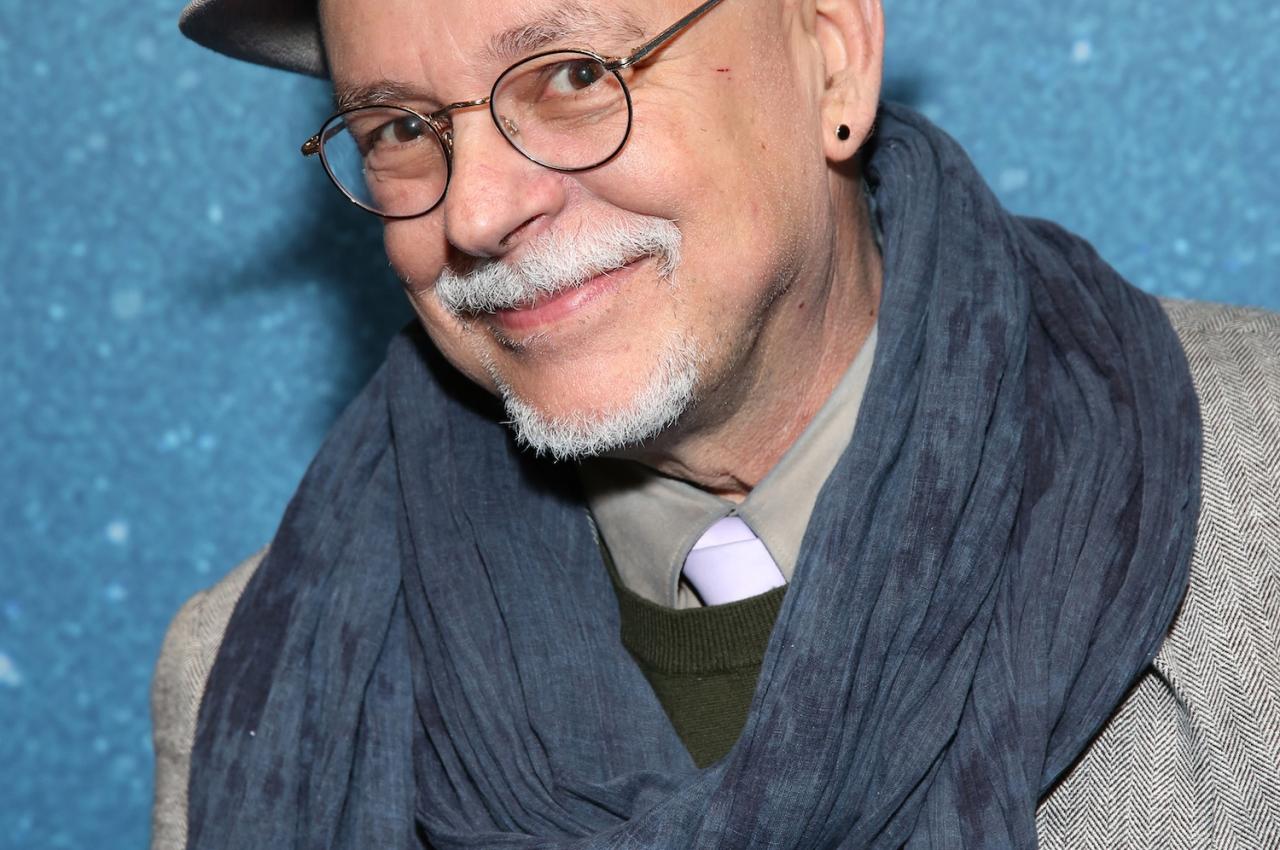

“Sheep and goats like to have twins, they’re built to make twins,” said veterinarian Rachael Gately. “There's some evidence that if you put in more than one embryo, there's a stronger chance of the ewe getting pregnant.” Photo: Alonso Nichols

‘Success Beyond Expectation’

In late January 2025, bundled in parkas, hats, and boots as snowflakes fell around them, Gately and her team prepared to implant the embryos into Hooper’s sheep. They would put two embryos into each of seven ewes.

“Sheep and goats like to have twins, they’re built to make twins,” Gately said. “There's some evidence that if you put in more than one embryo, there's a stronger chance of the ewe getting pregnant.”

Implanting the embryo is a surgical procedure in sheep and goats because their cervix cannot be traversed with an embryo transfer gun. (It is not a surgical procedure for horses and cattle, because their cervix can be traversed.) After many years of training and practice, and with veterinary technicians at her side to assist, the procedure takes Gately about 10 minutes per sheep, down from over an hour per animal when she started.

The industry standard success rate for pregnancy using frozen embryos is about 45%. In the case of Hooper’s flock, however, it was closer to 85%. Six of the seven ewes became pregnant, five of them with twins and one with a single lamb. Both women described the results as being far beyond their expectations.

“I wanted to do my part perfectly, following the provided instructions, because I really wanted us to have a good result,” said Hooper. “When Dr. Gately came out to the farm a month after the procedure to do the ultrasounds and see how many were pregnant, we were just over the moon, because she kept saying, ‘Pregnant! Pregnant! Pregnant!’ It was an outstanding result.”

The gestational period for a sheep is about five months, so in June, the ewes were ready to deliver their lambs. The night the lambing began, Hooper recalled sitting among the hay and sheep in the covered barn, where things started off smoothly—but soon took a turn.

The first ewe had her two lambs fairly easily and without issue. With the second ewe, the twins got stuck in the birth canal. Hooper called Gately, who rushed over in the middle of the night.

“When Dr. Gately came out to the farm a month after the procedure to do the ultrasounds and see how many were pregnant, we were just over the moon," said Judith Hooper. "She kept saying, ‘Pregnant! Pregnant! Pregnant!’” Photo: Courtesy of Judith Hooper

“I swear she's got eyes on the ends of her hand, because she reached in, untangled the twins, and pulled them out,” said Hooper. “But they weren't breathing.”

Gately administered doxopram, a medication that stimulates respiration.

“Within five minutes they were up and nursing. These are the most robust lambs I have ever had,” Hooper said.

Flocks for the Future

Gately called Hooper “smart and strategic” in how she chose which embryos to put in which sheep, because the result was multiple different lineages of purebred Herdwicks. It takes 1.5-2 years for females to reach a breeding age. Going forward, Hooper can breed Herdwicks herself and collect and sell their genetic material.

In total, Hooper’s sheep gave birth to 7 males and 4 females. Hooper is hoping to sell the rams to other people who need sound genetics for their own upbreeding programs. The new ewes will stay with her, and she expects to do another round of embryo transfers with the same six ewes that gave birth this year. She already has a waiting list for people who would like to buy purebred Herdwick ewes.

“With them comes the hope of developing many new purebred Herdwick flocks across the USA,” Hooper said.

Preserving biodiversity and these rarer breeds of sheep is a major goal—one that Cummings School has long supported. For 20 years, the school collaborated with the Swiss Village Farm (SVF) Foundation and, in 2022, completed the SVF Biodiversity Preservation Project. More than 100,000 samples of semen, embryos, blood, and somatic cells of more than 1,100 animals across 36 breeds of cattle, goats, and sheep were collected, cryopreserved, and stored.

SVF’s “seed bank” of frozen material also protects the world’s food supply. Preserving an array of livestock breeds that can thrive in hot, humid, or arid climates means people could have access to food no matter where they live.

Improving the genetics and durability of sheep in the U.S. is another goal. Take the Suffolk breed, for example. Suffolks in the U.S. are tall, don’t have a lot of body mass, and are a little fragile—"but very pretty, the classic sheep,” Gately added. In the U.K., the same breed is more durable. They’re situated low to the ground and are rugged with tremendous bone diameter. Gately said some people want to bring those genetics here to make our breeds better.

Another goal is to contribute to environmental sustainability, Hooper said, as the Brillo-like wool of Herdwick sheep has multiple uses as a biodegradable natural fiber that does not contribute to microplastics.

“Sheep fleece in general is a great fertilizer and great mulch. It's used for stabilizing erosion-prone and marshy areas in the U.K., where it’s also used as insulation for buildings since it breathes,” said Hooper. Gately added the wool is so coarse that it’s even used to make small furniture.

Judith Hooper expects to do another round of embryo transfers with veterinarian Rachael Gately, and there's already has a waiting list of people who want to buy future purebred Herdwick ewes. Photo: Alonso Nichols

Training the Next Generation

Veterinary field work can be physically demanding in many ways, from lifting animals to carrying equipment to performing mobile surgeries.

“I still have neck and shoulder pain from when I got trampled by a cow in 2019. Last fall I got hit on the head by a sheep, which kind of compounded other injuries,” said Gately. “Some of us damage our rotator cuffs with all the rectal palpation we do on cattle and horses.”

Gately needs a lot of help to do what she does, but luckily, she has a strong team. On the day of the embryo transfers at Grass Hill Farm, Gately was joined by her TVFS colleague, Adam Ward, D.V.M., as well as Cassidy Narkawicz, one of three large animal veterinary technicians at TVFS.

She also has a steady supply of fourth-year veterinary students, who all have the opportunity to go through the field service rotation. Some students go on the road with the veterinarians in the team’s mobile surgery trailer.

“While the animals are sedated and I’m using the laparoscope to look into their abdomen, I’m usually able to let the students look in, too, which they often think is cool and intriguing. There’s a camera on the laparoscope so they can see what I'm doing.” said Gately. “I think that even the students focused on small animals can relate, because laparoscopy is a part of their world, too.”

Gately and her colleagues always give the students a role in the procedure whether it’s sedating and monitoring the patient, performing the surgical preparation, or administering post-operative medications. Two veterinary students were with her on the day she transferred the embryos into Hooper’s ewes.

“It was one of those days that ended up going way more seamless than it had any right to,” recalled Joshua Wen, D.V.M., V25. “Everything flowed like clockwork, like it had been rehearsed. To top it off, it began to snow as we finished up, and I swear that on the drive back to the clinic, it became apparent that Judy’s property was the only place it snowed that day.”

Gately said some veterinary students are particularly interested in the TVFS team’s ART work and will reach out ahead of time to schedule their rotations during their busy season, which is the fall into winter. However, the students aren’t the only ones who are grateful for a front-row seat in Gately’s mobile classroom.

“Dr. Gately and her fabulous team helped me have a pragmatic vision for what can be done with my sheep, and when, and what the protocols are,” said Hooper. “Whether it's artificial insemination or embryo transfer, it is always done here on the farm. I get to see what's happening and they let me be part of it, which is wonderful.”

Latest Tufts Now

- Can AI Be Conscious?Experts debate the possibility at a symposium in honor of Daniel Dennett, and most agree it’s not a good thing

- What Happens When Neighborhood Pharmacies CloseSchool of Medicine experts explain pharmacy deserts and how consumers are impacted by thousands of shuttered drugstore locations

- The Wizard Behind WickedHow Gregory Maguire, AG90, created the story that inspired the blockbuster musical and movies

- Tufts Watchlist and Playlist Recommendations Fall 2025Check out three dozen TV shows, podcasts, films, and musical albums recommended by Tufts University faculty and staff

- Tufts Dean Named to National Academy of MedicineChristina Economos’ focus on team-based nutrition research demonstrates the direct and critical relationship between food and health

- Women’s Rowing Wins Third Straight Head of the Charles Collegiate Eights TitleMen’s rowing takes second place in Collegiate Eights, runner-up behind Division I College of the Holy Cross