The Gulf of Maine Is Warming Faster Than Pretty Much Anywhere Else

Spanning roughly 36,000 square miles, stretching from Cape Cod in the south to the Canadian province of Nova Scotia in the north, the Gulf of Maine is a vast ecosystem teeming with life. Its waters, traditionally colder than the nearby waters of the Atlantic Ocean and rich with phytoplankton and kelp forests, have long been home to marine species as diverse as the humpback whale, the harbor seal, the American lobster, and the Atlantic cod.

But today this extraordinary ecosystem and the communities that rely on it are under threat. The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than 95% of the world’s oceans, a disruption with far-reaching consequences. Water expands as it warms—and, coupled with melting glaciers and ice sheets—causes sea levels to rise. This increases the likelihood of severe flooding that can damage working waterfronts and coastal communities.

Warming water also affects the marine organisms that call the gulf home. Migration patterns are changing, with lobsters shifting farther north and farther offshore. Relationships with predators are changing too; green crabs, which thrive in warmer waters, are feeding voraciously on clams, oysters, mussels, and other local species.

To respond to these serious and fast-moving challenges, the Gulf of Maine Research Institute (GMRI) in Portland, Maine, is deploying research and piloting a range of programs to help municipalities, businesses, and concerned citizens meet the realities of the climate crisis.

That work has implications well beyond the immediate region. “Because warming is happening so quickly in the Gulf of Maine, we are starting to see the impacts on the ecology and fish faster than other areas,” says Dave Reidmiller, chief impact officer at GMRI. “It forces us in many ways to accelerate actions and adaptation strategies. We are developing solutions that have the potential to meet the climate crisis head on, and the lessons that we learn we are sharing with fishing communities around the world.”

Among those leading the way are four Tufts alumni. With the working waterfront of Portland just steps away, where fishing and lobster boats crowd historic wharfs and tourists line up outside seafood restaurants for fresh seafood (and lobster specials), their workplace has a front-seat view of Maine’s economy and way of life.

To support community resilience in face of the climate crisis, these leaders bring their expertise to bear on product design, local food systems, and community planning, pursuing each activity with pragmatic optimism. Together, they are shaping a vision of the region as well prepared for both the challenges and opportunities of climate change.

Promoting Sustainable Seafood

The link between Maine’s coastal economy and the Gulf of Maine is evident throughout Portland’s working waterfront of piers and wharfs. Commercial fishing vessels harvest a remarkable diversity of fresh seafood, from crab, oysters, lobster, and scallops to white fish such as flounder and halibut.

In recent years, though, commercial fishing sectors like cod and haddock have been hard hit. Complex challenges include changing harvest regulations, climate impacts, and intense competition from imports, with countries like Iceland and Norway being significant suppliers of less-expensive frozen fish and seafood. Tariffs that the U.S. has recently proposed might make imported fish more expensive and help local producers compete, but the import taxes also could raise prices for some local harvests, such as lobster caught in Maine and processed in nearby Canada.

To support local producers, Kyle Foley, N12, director of GMRI’s Sustainable Seafood Program, aims to “raise awareness about the amazing diversity, health benefits, and deliciousness of fish and shellfish. It’s a win-win-win: choosing local supports healthy coastal communities, a healthy ocean ecosystem, and healthy people.”

She helps consumers to find and buy Gulf of Maine seafood through outreach efforts like Your Guide to Local Seafood, an interactive map of regional restaurants and retailers that are part of GMRI’s Gulf of Maine Tastemakers program. Tastemaker members (including Tufts Dining) are committed to buying at least 35% of their seafood from regional sources.

A grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Saltonstall-Kennedy Program helped Foley build relationships with restaurants, schools, and major retailers and promote local, responsibly harvested seafood “right here in our backyard,” she says. Part of the effort involves inspiring people to try a wider variety of seafood. “It sustains and strengthens the seafood industry if there is demand for a more diversified portfolio of species,” she says.

Attitudes are changing, says Foley, who joined GMRI in 2013. She cites GMRI's Sea to School program, an outreach initiative involving New England K-12 schools. One school district doubled its local seafood purchasing after participating in the program, while another served five times as much local seafood as it did in the previous two years, she says.

“We also partnered with Congolese, Cambodian, and Iraqi immigrant chefs from the Portland area to develop four seafood recipes for K-12 schools using influences from their cultures to present culturally diverse options for all students,” she says. “And we developed a seafood curriculum for middle school students, which has been taught across eight school districts in Maine so far, and we continue to expand its reach.”

All these efforts help build demand for regional seafood, which helps seaside communities thrive. “The seafood industry, whether harvesting lobsters or crabs or cod or clams, has long been the lifeblood of New England,” Foley says. “Our work is all about ensuring it has a strong future.”

Blue Economy Entrepreneurship

As the traditional seafood industry evolves to respond to changing circumstances, entrepreneurs are looking for new ways that the Gulf of Maine can support the regional economy. For example, kelp harvested from local waters might be used in everything from veggie burgers to smoothies. But translating such ideas into successful businesses can be a challenge.

That’s where Jeff Bate, EG12, can help. As senior product manager with Gulf of Maine Ventures, GMRI’s entrepreneurship and innovation team, he supports early-stage blue economy companies (anything ocean-related) with mentorship, science and industry expertise, and connections to partner resources.

Kelp, or seaweed, offers a full plate of planet-friendly benefits, he says. It’s not only good for ocean health (it removes excess carbon) and humans (it’s a nutrient-dense superfood), “but it also offers traditional fishers a business opportunity with a high potential for growth.”

Entrepreneurs are interested in seaweed not only as a healthy food, but also as an additive to a range of products including biopharmaceuticals and packaging materials, says Bate, who joined GMRI in 2016. “As part of building a climate-resilient future, kelp farming is a promising piece of the puzzle.”

Bate also helps develop educational experiences for LabVenture, GMRI’s premier education program. Some 9,000 fifth and sixth graders from every county in Maine—about 70% of the state’s middle schoolers—visit GMRI each year to explore its rich variety of hands-on activities (including measuring a live lobster).

Field trips start off with looking at plankton through a microscope, and then identifying different plankton species projected, via a camera feed, on an illuminated table. Another activity has students study data from NASA satellites and research vessels, which is linked to learning how warming waters are causing lobster to migrate north.

The learning environment aims to inspire the next generation of entrepreneurs, scientists, and community leaders by teaching them about the challenges facing their region and how they can make a difference. “For two and a half hours they’re immersed in a combination of tactile and group work and technology-driven exploration,” Bate says. “We want to give them knowledge and curiosity that they’re excited to explore back in the classroom and beyond.”

Supporting Community Planning

On the morning of January 13, 2024, Stephanie Sun, AG23, pulled on a pair of rain boots and joined colleagues as they set out to gather data at high tide monitoring sites that are part of the GMRI’s Coastal Flood Monitoring Project. It was not going to be business as usual.

Colliding with the highest predicted tides of the year was a powerful storm surge; by the time the day was over, the high tide would exceed 14.5 feet, the highest ever recorded in Portland. Maine’s governor estimated that the storm, along with another storm earlier that month, caused $70.3 million in public infrastructure damage, particularly in the state's eight coastal counties.

“We were surprised at what we saw in real time,” says Sun, a climate engagement specialist with GMRI since 2023. She recalls standing atop a cement block on Portland’s Union Wharf, where the water had risen some two feet.

“I realized, it’s one thing to witness such an event firsthand and it’s another to know that people living in more than 140 coastal communities were having the same experience and wondering: ‘What can we do to prepare for the next time?’” she says. “This storm was going to serve as a flashpoint for many communities to start to want to take more concrete actions in managing storm impacts and the damage they cause.”

Indeed, both high tide flooding and storm surge flooding are expected to get worse as climate change warms the ocean and contributes to ongoing sea level rise around the world. Given the accelerated warming of the Gulf of Maine, more frequent and more severe coastal flooding is predicted to increasingly threaten coastal areas, both rural towns and major cities.

By focusing on community housing, transportation, and community wellbeing, Sun support coastal communities and blue economy businesses with the knowledge, tools, and confidence they need to build climate resilience. Municipal staff and volunteer committees, for instance, increasingly want to incorporate sea level rise projections into town planning.

“Communities are thinking what's important to them to protect, what their priorities are for climate resiliency,” she says. “We take a broad approach, recognizing that climate impact isn’t just about infrastructure; it’s also recognizing where climate intersects with housing and education and bringing that full picture into sharper focus.”

Community connections are growing. GMRI’s Community Science Project allows people up and down the coast to submit photos of flooding as well as narratives. This coastal flooding community science helps GMRI visualize data and provides residents with guidance on developing localized flood thresholds to inform local decision-making and emergency management.

“We want to support communities in identifying their priorities and values so that they can make decisions themselves,” says Sun.

Steps that advance resilience are always evolving. They’ve included a vulnerability assessment for Tremont, a town on the southwestern side of Mount Desert Island with a waterfront that’s integral to the local economy because of its fisheries, boat building, and tourism.

Sun enjoys sharing her facilitation and planning expertise to help such communities, which are “ready to put it to practical use,” she says. “When the next storm comes, they want to be ready.”

Collaborating on Fishery Management

Climate change brings forward complex economic and ecological fishery issues that Lauren O’Brien, N17, hears about directly from the people most affected: fishing communities, including recreational, charter, commercial, and subsistence fishers.

At the same time, creating solutions for climate resilience and readiness are one focus of eight federal Fishery Management Councils that manage federal water fisheries within their respective regions.

Councils incorporate ecosystem and climate information when considering how to set regulations that ensure long-term sustainability. Climate-related factors driving those decisions, for example, include how marine heatwaves may contribute to the decline of Pacific Cod in the Gulf of Alaska and the collapse of eastern Bering Sea snow crab.

As senior manager of GMRI’s Marine Resource Education Program (MREP), O’Brien, who joined GMRI in 2018, brings resources together to bridge the concerns of the fishing community with the evolving management strategies of the Fishery Management Councils.

With a sharp focus on strengthening communication channels, she organizes workshops in the regions she oversees: the West Coast, the North Pacific, and the Western Pacific. Her colleagues at GMRI manage the Greater Atlantic, Southeast, and Caribbean regions.

Workshops give participants the tools, knowledge, and relationships they need to effectively navigate fisheries science and management and have a say in regulatory reviews and decisions that directly impact their food sources and livelihoods. O’Brien’s role encompasses developing curricula and outreach strategies and supporting experts as they prepare presentations. She is informed by the regional Steering Committees she leads and facilitates, as well as communications with specialists and advisors, like those at NOAA Fisheries and the respective regional Fishery Management Councils.

“Many of the people I speak with are holding onto traditional fishing practices that go back generations,” she says. “The need for new strategies and regulations that allow them to adapt to climate change has never been more crucial. It’s important that their voice is heard. They have incredible insights and need to be a part of the solution to fisheries management challenges. MREP makes it possible for them to know how and when to get involved.”

O’Brien emphasizes that a shared value across the program is respect for the diverse viewpoints within each fishery management region.

“Collectively, we support all fishers through an objective education designed to bring people together to collaborate more effectively toward mutual goals,” she says. “It’s work that’s never been more urgent. Adapting and managing our fishery resources sustainably is essential if we want to ensure the health and stability of the fishing industry and fishing for cultural and subsistence value.”

Latest Tufts Now

- Cells Have a Second DNA Repair Toolbox for Difficult CasesCancer cells may rely heavily on backup mechanisms of DNA repair, presenting a vulnerability for targeted treatments

- Putting Science at the Forefront for the Next GenerationArea high school students learn biomedical engineering by working with graduate students and faculty in Tufts labs in a free summer program

- Am I Getting Enough B Vitamins?Make sure to take in the right amount, but not too much, of these eight key nutrients, according to a Tufts nutrition expert

- ‘I Never Looked Down on Any Job I Had’A carpenter and longtime member of the Tufts Facilities team on taking pride in one’s work

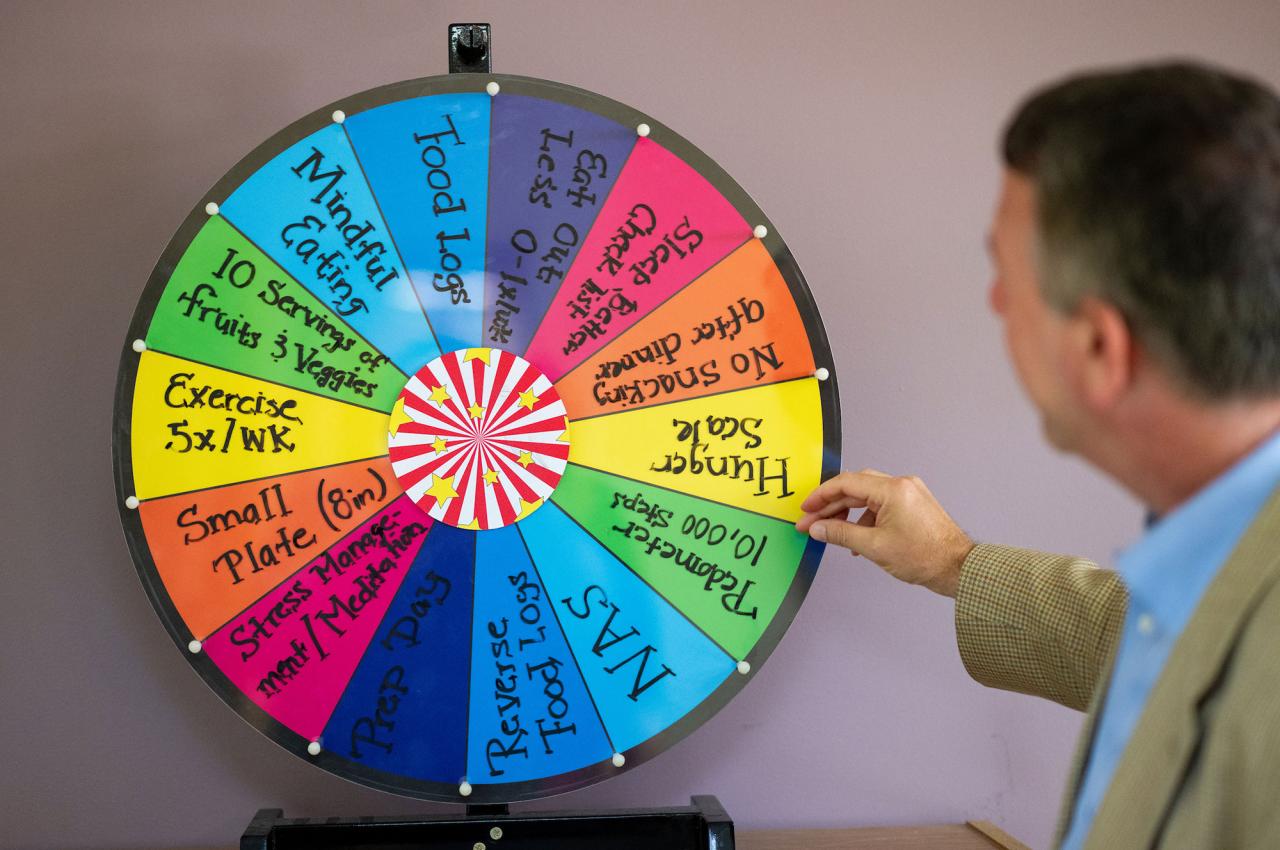

- For Some, ‘Group Magic’ Is the Key to WellnessHere's what happened when a family medicine physician and a dietitian teamed up to help groups of participants develop better health habits for life

- How B Vitamins Can Affect Brain and Heart HealthThese eight nutrients can have an impact on dementia, cardiovascular disease, and more, according to Tufts researchers