Breaking Through Political Polarization

Aram Hur remembers the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, partly because her father, a civil servant in South Korea’s Ministry of Finance, was seldom home during that time.

Hur once asked him why he was working so hard instead of spending time with her. His response—that South Korea was a remarkable nation that had overcome greater challenges in the past and that it was his duty to help overcome the current crisis—left a lasting impression. It shaped Hur’s understanding of nationalism as something greater than an abstract political force; she came to see it as personal and potentially unifying.

Today, Hur is the Kim Koo Chair in Korean Studies and an assistant professor of political science at The Fletcher School. Born in South Korea and having spent her school years moving between there and the United States, she developed a distinctive perspective on political polarization in both countries. Her research today explores how national identity shapes civic trust and democratic resilience, suggesting that, despite nationalism’s negative reputation since World War II, it can, when properly leveraged, strengthen democratic engagement.

“Typically the relationship between nationalism and democracy is seen as dangerous and negative,” Hur says. “The idea is that too much nationalism not only damages liberal democracy but is even antithetical to it.” Yet South Korea offers an example of a country that successfully cultivated a strong sense of nationalism and relied on it to build a democratic system, she says. “Many of its current democratic troubles,” she adds, “are rooted in the fracturing of that national unity.”

On Thursday, February 13, Hur will elaborate on these ideas at a Tufts panel hosted by the Office of the Vice Provost for Institutional Inclusive Excellence. The panel, "Engaging Differences Across the Political Spectrum," will feature faculty members discussing how to foster dialogue amid increasing polarization.

In anticipation of the event, Hur sat down with Tufts Now to highlight four elements she believes are necessary for addressing political polarization.

Awareness of the Other Side’s Sense of Threat

One of the central challenges in political polarization, Hur says, is recognizing that opposing political factions often perceive each other as existential threats. This occurs when partisan divisions are centered on national identity rather than just policy disagreements, as is increasingly the case in the United States, according to Hur. Both the left and right see each other not just as political opponents but as threats to what it means to be American.

This shift has created a dynamic in which ideological clashes trigger strong defensive reactions. “When you’re engaging with somebody from the other side,” she says, “it’s important to recognize the psychology of identity that can ignite a fight-or-flight response.” Instead of dismissing opposing views as irrational or partisan-driven, she suggests that individuals acknowledge the underlying fear of losing one’s place that is fueling polarization. Doing so can foster more productive conversations that address the root causes of division rather than escalating tensions.

Recognizing Larger Commonalities

Even as political factions battle over what it means to be American, Hur argues that the intensity of these debates underscores a fundamental commonality: both sides care deeply about the future of the nation. Throughout American history, periods of extreme polarization have often been mitigated by rediscovering shared national values.

“I might be a Republican and you might be a Democrat, but we are both American—even if we might fight about what it means to be a real American,” she says. “The only reason we’re in that fight is because we both care intensely about being American.” Recognizing this shared investment in the country’s identity and future can help temper the instinct to view political opponents as enemies, Hur explains, and instead reveal them as fellow citizens engaged in a shared democratic project.

The Responsibility of Leaders (and Voters)

Finding common ground is difficult when political leaders themselves fuel division, Hur points out. While grassroots efforts matter, she stresses that the rhetoric and behavior of party elites often set the tone for broader political discourse. “The onus is on our political leaders first,” Hur says. “Both parties need to recognize that while the differences are real and seemingly insurmountable at times, the only reason they exist is because both sides fiercely care about America—whatever version of America that might be.”

But it’s a little bit of a chicken-and-egg situation, she notes. If citizens want leaders who create the conditions for unity, they must create the conditions that incentivize those leaders to act. “The incentives for politicians to change ultimately come from people,” Hur says, “and their votes.” Encouraging a shift in leadership behavior requires voters to reject divisive rhetoric, foster a political culture that rewards cooperation over conflict, and support candidates who prioritize national unity.

Rethinking Nationalism

At the heart of Hur’s work is a provocative question: What if nationalism, rather than being a threat to democracy, could be part of the solution? While nationalism is often associated with exclusionary or authoritarian tendencies, Hur argues that it can also be a force for democratic resilience when properly harnessed. “The key takeaway is not to shy away from nationalism,” she says. “It’s not that we have too much of it; it’s that we don’t have enough of the right kind.”

To cultivate the right kind, Hur believes the United States—and other democracies—must engage in positive nation-building. Democracies must shed their wariness of nationalism’s darker historical associations and begin actively fostering a unifying national identity. That identity could be one that embraces a broad and diverse understanding of what it means to belong to a particular country, she says—and could help strengthen civic cohesion.

As she puts it, “No party is ever going to be perfect and no policy is ever going to satisfy everyone. But what’s important is how the full network of policies work together to signal a clear and consistent message about what this nation stands for and who belongs to it.”

Latest Tufts Now

- Tufts Veterinarian Helps Produce First Purebred Herdwick Sheep Born in U.S.Years of planning, precision timing, and the persistence of a local farmer culminated in the birth of 11 lambs this summer

- Can AI Be Conscious?Experts debate the possibility at a symposium in honor of Daniel Dennett, and most agree it’s not a good thing

- Tufts Dean Named to National Academy of MedicineChristina Economos’ focus on team-based nutrition research demonstrates the direct and critical relationship between food and health

- What Happens When Neighborhood Pharmacies CloseSchool of Medicine experts explain pharmacy deserts and how consumers are impacted by thousands of shuttered drugstore locations

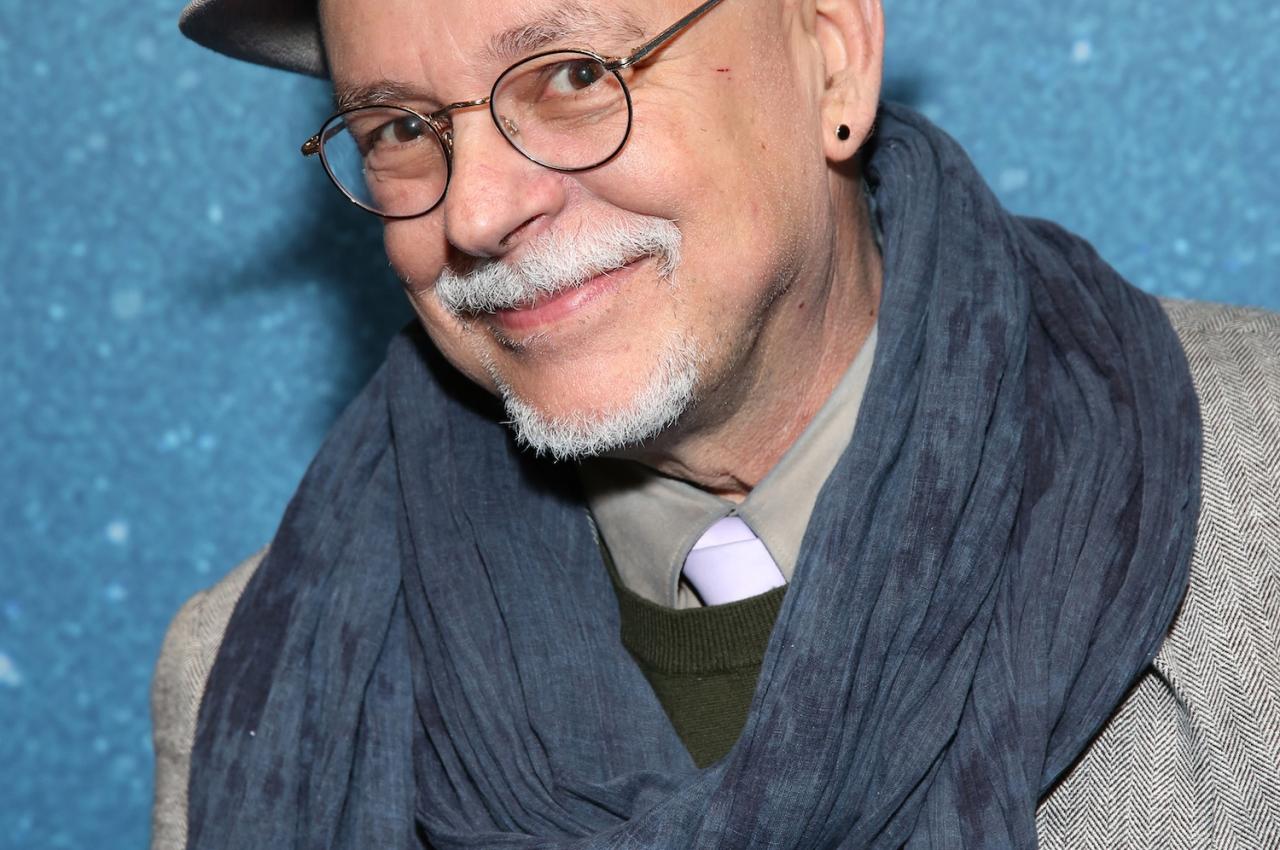

- The Wizard Behind WickedHow Gregory Maguire, AG90, created the story that inspired the blockbuster musical and movies

- Tufts Watchlist and Playlist Recommendations Fall 2025Check out three dozen TV shows, podcasts, films, and musical albums recommended by Tufts University faculty and staff