Inviting Empathy: A Mission to Address Anti-Jewish Harm

When talking about antisemitism, the Jewish training and support organization known as Project Shema doesn’t always rely on the term antisemitism.

“We often shift our language from the word ‘antisemitism’ to the frame of ‘anti-Jewish harm,’ says Zach Schaffer, Project Shema’s co-founder and vice president of community engagement. “We want to be able to identify and describe ideas and actions that erode safety and inclusion, and we think this can depolarize this conversation in a lot of ways.”

Project Shema (pronounced Sh’ma, the Hebrew word for “hear”) has been engaged by Tufts this spring for a two-part workshop at Tufts to support inclusion and belonging for the Jewish community. The events have been sponsored by the Office of the Vice Provost for Institutional Inclusive Excellence, Tufts University Chaplaincy, and Tufts Hillel as part of the Tufts Inclusive Education Series (TIES).

The first session took place online on March 27, and an in-person follow-up dialogue session took place on the Medford/Somerville campus on April 6. Each of the workshop’s two parts were open to all undergraduates and graduate students at Tufts.

In its work, Schaffer says, Shema offers a “tone and tenor of conversation that really invites everyone in, regardless of their values, of their political identity, or of the contexts and communities that they exist in.”

“We create a space where everyone feels welcome, everyone feels heard, and everyone can be empathized with,” he says. “And we can do that while still grappling with the most difficult questions.”

Schaffer spoke with Tufts Now about the work of Project Shema.

What does Project Shema mean when it talks about antisemitism or anti-Jewish harm?

Project Shema has never endorsed or promoted any other organizations’ definition of antisemitism in our work. We’re helping participants have the empathy, the understanding of Jewish lived experiences and of how anti-Jewish harm happens, so that our participants can identify anti-Jewish harm themselves, unpack their own anti-Jewish biases, and change and challenge their biases about Jews.

Rather than a one-size-fits-all definition of antisemitism, we shift the focus to explore what anti-Jewish harm looks like. Our focus is on disrupting ideas and actions that undermine individual and collective Jewish inclusion and safety, and to do that in a way that nurtures safety for everyone.

What are the specific dimensions of antisemitism, and how is it similar, and different, from other types of hatred?

One way we understand antisemitism is as a systemic bigotry that has existed for thousands of years, and that we are all socialized and conditioned into. No one is exempt from having biases or bigotry about Jews. They’re in the fabric of our society, and this is one of the ways in which antisemitism, or anti-Jewish harm, ideas are similar to some of the other forms of hatred and bigotry.

One thing that makes antisemitism different than some other forms of harm is that antisemitism is not only a systemic bigotry, but it is also a conspiracy theory, an ancient and malleable conspiracy theory that includes a set of ideas about Jews, and motifs about Jewish power, Jewish untrustworthiness, Jewish corruption and greed, and Jewish evilness. These ideas always morph to meet the moment in different cultures.

We understand antisemitism is something that, of course, harms Jews. And in our workshops, we help people understand the unique ways in which antisemitism undermines collective Jewish safety. We also understand antisemitism as something that fuels white supremacy, undermines democratic institutions, and erodes pluralism, making everyone in society less safe, especially marginalized communities.

How long has Project Shema been doing this work?

We were founded in 2022 by Jewish leaders, including myself, with deep ties in social justice movements. We had been working on curriculum and learning a couple of years prior to that.

How, if at all, did the events of Oct. 7, 2023, affect your mission or the way you did outreach?

Our mission has always been to stop the normalization of ideas that undermine collective Jewish inclusion and safety. And we’ve always believed that collective Jewish safety can only be ensured within healthy and pluralistic societies. Since October 7, the need for this work has grown tremendously. Jews are experiencing a terrible uptick in demonization, exclusion, and harm. And since October 7, more and more friends outside of our community are understanding the need to show up as allies. So, we are expanding our work with allies and meeting their need for a compassionate, nuanced, depolarized conversation about Jewish identity and antisemitism.

Who are your audiences?

We work with both Jews and non-Jewish audiences. A lot of our work in this moment has been with non-Jewish partners, colleagues, and communities, and we have been incredibly grateful over the last couple of years to see so many people eagerly show up to our workshops in every context to build their skills as friends and allies. They do the hard work of unpacking their own biases and trying to better understand our community’s lived experiences, diversity, traumas, and experiences of harm.

Often our partners are relieved to be able to enter such a difficult and, at times, politicized and polarized conversation in a way that contains so much curiosity, compassion, grace, and nuance.

Project Shema's website talks about “new ways to engage peers who don't wish to harm the Jewish people, but may accidentally perpetuate anti-Jewish harm.” Can you expand on that?

I believe we’re all socialized into anti-Jewish prejudices and biases, and that none of us is exempt from the cultural conditioning of anti-Jewish ideas. I do not understand antisemitism as just a sentiment—one does not have to have malice toward Jews, or hatred toward Jews, to believe ideas about Jews that are harmful or that are grounded in unconscious or implicit bias or conspiracy theories. While I have met people who hate Jews, and I have personally experienced aggressive antisemitism, I have found in most of our work that most people do not wish to cause harm and do not have the context necessary to understand the impact of their language or actions.

So when I meet someone who perpetuates anti-Jewish harm with their language or actions, I recognize they may not have hatred or malice toward Jews and they may not be aware that their actions or language are even causing any harm. This is why we approach all of our partners and participants with unbearable compassion and unwavering grace.

When you say “we’re all socialized into anti-Jewish prejudices and biases,” would you include Jews in that group?

Living in society means we are all, including Jews, going to be socialized into certain ideas about who Jews are and what Jews look like and what it means to be Jewish. So we certainly all have to do the work to unpack, change, and challenge those biases. No one, including me, is immune to these ideas.

Latest Tufts Now

- Cells Have a Second DNA Repair Toolbox for Difficult CasesCancer cells may rely heavily on backup mechanisms of DNA repair, presenting a vulnerability for targeted treatments

- Putting Science at the Forefront for the Next GenerationArea high school students learn biomedical engineering by working with graduate students and faculty in Tufts labs in a free summer program

- The Gulf of Maine Is Warming Faster Than Pretty Much Anywhere ElseThese researchers are hurrying to help coastline communities and economies adapt to the changing waters

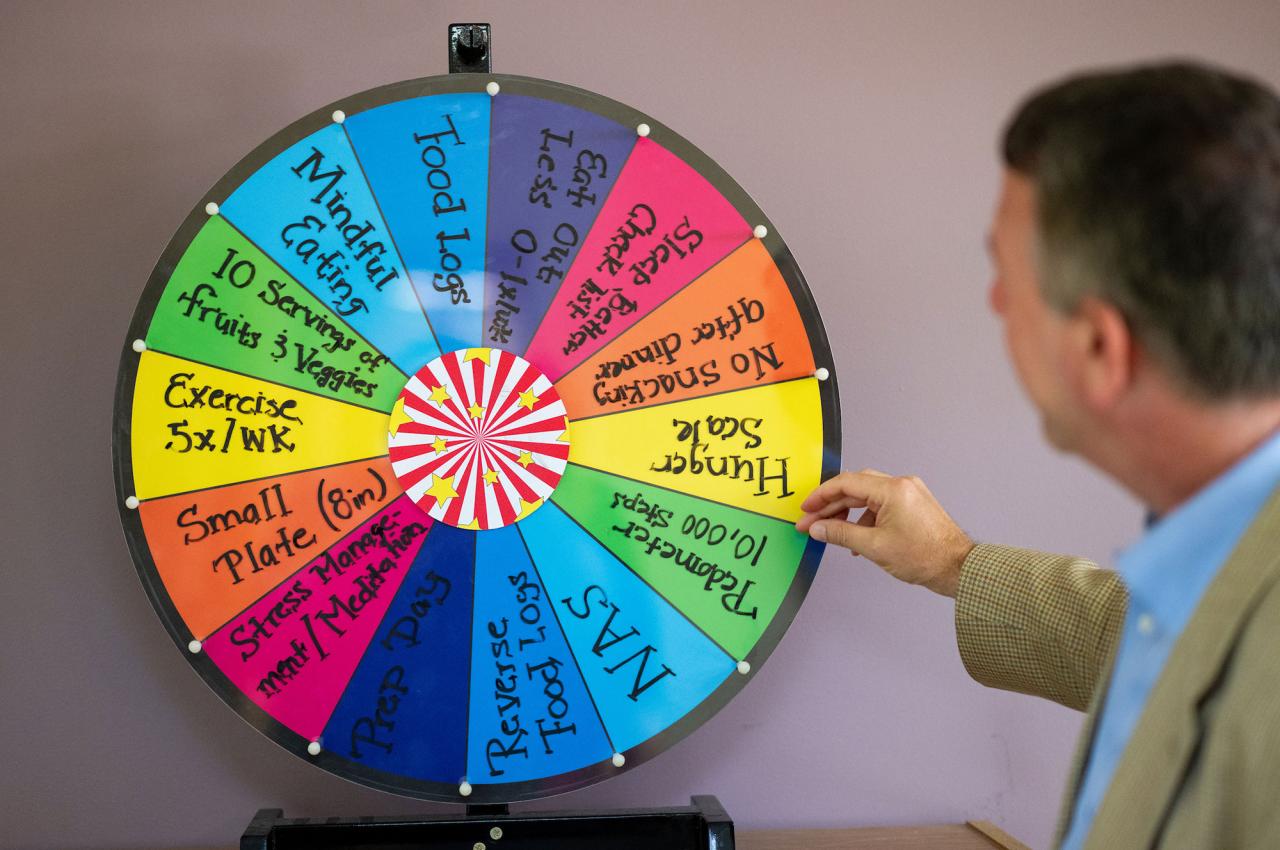

- For Some, ‘Group Magic’ Is the Key to WellnessHere's what happened when a family medicine physician and a dietitian teamed up to help groups of participants develop better health habits for life

- Am I Getting Enough B Vitamins?Make sure to take in the right amount, but not too much, of these eight key nutrients, according to a Tufts nutrition expert

- ‘I Never Looked Down on Any Job I Had’A carpenter and longtime member of the Tufts Facilities team on taking pride in one’s work